Brené Brown: Hi, everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is the Dare to Lead podcast. Oh, God, I cannot tell you how excited I am about this conversation. I have heard about Dr. Pippa Grange from so many people, and during the podcast, we realized that we named it, we have been crossing paths spiritually for many years, working with some of the same people, and at some of the same conferences. She is a very highly sought-after sport psychologist and culture coach. She is the author of the best-selling book, Fear Less: How to Win at Life Without Losing Yourself. I first heard about her, like many people hear about her, that she was the Head of People and Team Development at the Football Association in the UK, meaning for those of us in the U.S., the soccer teams that she worked with the England team for the World Cup in 2018.

BB: She’s just done this incredible work and she talks so brilliantly about perfectionism and fear and anxiety, and clenched fists versus open hearts, and I can neither confirm nor deny that it’s a pretty emotional podcast for me in spaces. So I’m glad you’re here to learn with us. Welcome to the Dare to Lead podcast.

BB: So let me tell you who Pippa is before we get started. It’s Dr. Pippa Grange, she’s a sport psychologist, a culture coach, working across elite sports and businesses internationally. As the Head of People and Team Development at the Football Association, she worked closely with the England team for the World Cup in 2018, a performance that united the nation and inspired a new narrative on the sheer joy of competing with less fear and less ego. I always think of her as someone, part of the team, that helped break the penalty kick curse, she’s just a brilliant thinker about performance, and two other words that we don’t hear that we do need to start joining with performance: love and soulfulness.

BB: She believes relationships are at the heart of everything and the antidote to fear, she is currently the Chief Culture Officer at Right to Dream. She is particularly invested in ensuring opportunities for women and girls and is passionate about finding a different archetype for women working in sport and other male-dominated areas. She was born and raised on a council estate in Yorkshire by her mom. At age 25, she moved to Australia where she lived for 20 years, following some time in LA, and she now lives in the very glorious Peak District with her husband and two dogs. If you’re looking for me after the pandemic, you will find me in the Peak District with Pippa and the dogs and her husband, I think she described it, around a fire pit with some s’mores looking out on the moors of Yorkshire, which y’all know that I’m obsessed with.

BB: So first, let me say, thank you so much, Pippa, for joining us on the Dare to Lead podcast. I’ve been really looking forward to our conversation.

Pippa Grange: Thank you for having me, I’m so humbled to finally be talking to you and meeting you. I’m a big fan, and I’ve been looking forward to chatting to you for a long time.

BB: Thank you for that. And let me tell you how I had heard of you, and you were this mysterious person in the circles in which I run. Like, “Have you heard of the woman,” but I’m sure you’re going to know what this is, right? “Have you heard about the woman who ended the soccer team’s penalty kick curse?” And I’m like, “Yeah, I have.” And they said, “But have you ever met her? I mean, does she exist? What do you know about her?” And so, there was all this talk. And then I find myself in Melbourne, Australia, doing some work with the Richmond Aussie rules football team.

BB: And I’m not a sport psychologist by any stretch, but there was a sport psychologist kind of in the box with us watching the game, and he comes up to me and he said, “Do you know Dr. Pippa Grange?” And I said, “No, I know of her. Have you met her?” And he goes, “I’ve met her in real life. She’s amazing.” Yeah, yeah, I was like, “Wow.” And he’s like, “She’s as amazing as you think, you’ve got to meet her and the two of you would just hit it off, you would just get along so great.” So I am so excited that through all this mysterious conversation about you, I get to talk to you and I love… Yeah, and I love your book.

PG: Thank you, thank you. And I’m excited that you’re a Richmond Tigers fan, they’re one of my favorite teams of all time. I know that you went down and spoke to them last year and they loved it. They’re huge Brené people now. They’re just a fantastic, open hearted, whole-hearted team, it’s wonderful to see that when you get to see it. So that we have crossed paths spiritually, if not physically, until now.

BB: Yes. We have crossed paths spiritually. Okay, I want to start with this question. Tell us your story. Your story.

PG: Okay.

BB: From the beginning.

PG: From the beginning, that’s a 50-year story. But I grew up in England, in a place called Harrogate in North Yorkshire, and it was kind of a relatively straightforward early life, but it got more complicated through my later childhood and into my adolescence. We had some family difficulties with drugs, alcohol and domestic violence, and I ended up leaving home really young, 16 when I left home, and we had kind of an estranged time as a family from there. And at that point in my life, I was kind of lost. I didn’t really know who I was or where I was headed, but I had the very good fortune through some wonderful connections and some loving people to kind of recognize some things in me, like the fact that really I’m a nerd, my love of curiosity and learning was a pathway for me and a teacher convinced me that I had maybe what it took to go to university, which had never even crossed my mind as a young person, that was just… Nobody in my family had done anything like that, or nobody I knew had done anything like that.

PG: So that was kind of a wild idea. And then I attached to it and I thought, I’m going to see if I can do that. And I went to a university near called Loughborough, and it was a sports university, I did sports science and social science psychology, and I absolutely loved it, and I got into this environment full of different types of people than I had met before or spent time with before, and I had a sense of belonging in some ways, in some ways I didn’t, but I kind of forge a path. I played basketball at university as well, and really started an understanding of what sport could be in a person’s journey and what kind of anchor it could offer for belonging and for a connection and for a sense of yourself.

PG: And I had an opportunity when I did… The standard go travel for a year and find yourself post-uni, which was fun, and I went on my own, which was a real test for a year. I went to Australia and totally fell in love with that place. And then I had an opportunity a year or so later to go to Australia to live, to work for a couple of years, and I went, and if you like being outside and you like sport, this is an unmissable place, as you know, right? Melbourne particularly is just jaw-dropping in every way, I really love that place.

PG: And I kind of built a life there, and I picked up some more psychology qualifications, and I thought “I like this deal of working in sport psychology, I wonder if I could be a sport psychologist?” So I did a doctorate and worked all the way through alongside the study, and I just kind of forged a career. In my first sort of efforts in sport psychology, I worked for an organizational psychologist, and they had a contract with the AFL, and they had for players who may have difficulties. It’s hilarious now when I think back about it, but I was the person at weekends who had the footie phone.

BB: Oh, my God. Let’s stop for minute. So AFL is Australian Rules Football, right?

PG: Australian football, yeah, yeah.

BB: Right. So what’s the footie phone?

PG: Well, they had this idea that if a player was having any difficulty, they would just pick up the phone and call a random person that they didn’t know and tell them about it. And so you had to have this phone with you at all times, if you were in the cinema, you had to have it with you on silent, and this is back in the day when not everybody had a phone all the time.

BB: Right. You had the AFL bat phone.

PG: Yeah, I had the bat phone, and I think it went off once in the whole year or two years that I had the bat phone, and it was because a player had broken down on the highway and didn’t know who to call, RACV or the roadside assistance. I’m like, “You know, I really would like to help you, but this is outside my circle of competence.” Then I had really an opportunity for a job with the AFL Players Association, and they were at a state where they were wanting to set up psychology services for athletes and their families, so it was kind of like the stuff of life, not performance, it was somebody’s had a relationship break down or they have family difficulties or drugs or alcohol. And so I set up the psych services for them, and I worked for five years doing that and I just loved it and I was always athlete-centered in my approach, but it just really affirmed to me that the athlete is the hub, at the center of the wheel, and we should never forget the human being.

PG: So I did that for five years and totally loved it, and I had some battles in there with the kind of broader context of sport and particularly around how people treated addicts and around the lack of understanding of the humanity that goes with the athlete, and I decided after five years or so that, that was probably as far as I could go there, but I’d really lit a flame in me to work on the culture of sport by then. And so I kinda started my own business, which I did for eight years across individuals, organizations, sports, business, and I just really went into that culture coaching space, so I was working on how the organization works, I was working on the context, working on the conditions that allow somebody the freedom to perform or to be their very best.

PG: That was a long and winding road and I totally loved that work. I found myself in LA for a couple of years with a business client, and then eventually the English Football Association called and said, “We’re looking for somebody to run the people and teams, all of the sport psychology and the culture work for 16 England teams, men’s and women’s, and to work with the men’s team,” and I was like, “English football, are you crazy? Why would you do that?” Because it is a circus of shame, as you will know, as a football person there and the English media and football has been a very long battle. So at first I was thinking, “No, that’s a disastrous choice, a disastrous career choice, that’s an undoable job.”

PG: But the more I spoke to them, and the more that I understood how far they’d actually come already, and how much great work had been done on building systems for humans, systems to win as well, I got more interested in it and I decided to give it a go. And so my husband and I moved over here and we live in the Peak District in England, which we totally love, did this crazy couple of years with the FA in England, and during which time there was a World Cup and a penalty shoot-out, that kind of catapulted me, probably unfairly in lots of ways, because many people go into something like that, but I think people could feel the difference in tone, I think people could feel the players’ freedom and joy more. And it was so different that they looked for a cause for that difference, and it’s never one person, but I hope I did contribute to that.

PG: And things changed, there was a restructure, it was going to become more technical and less cultural in the work, and I decided that that maybe I wasn’t going to be where I really found my tribe. So I started work with the Right to Dream, which is where I am now as Chief Culture Officer. And Right to Dream is a football organization, but it’s an organization that offers opportunities through education, character development, and football for students. We have an academy in Ghana and a football club in Denmark, and we’re just about to open another academy in Egypt. The purpose of the organization is to redefine excellence, so I kind of feel like I’ve found my kindred spirits, finally, who want to work on the paradigm of sport, not just the individual people within it. So that’s kind of the story. And in the meantime, my beautiful husband Ablaye and a couple of dogs, here in the Peak District in the middle of England.

BB: Beautiful, thank you for sharing that with us, I was so curious about your journey. Can I ask a couple of questions, can I dig into the story a little bit and ask some questions?

PG: Of course, yeah, please do.

BB: You bring a soulfulness to your work. Is that fair to say?

PG: I hope so.

BB: Yeah, a soulfulness, and I’ve worked with professional athletes and teams, soulful’s not always the first word that would come to mind for me. What did you hear specifically from the England football club that hooked your interest, and what would they have said that was a red flag? Tell me just as someone who goes in and does this work, what were the kind of things that you heard or you still hear that make you hopeful, and what are some of the flags that would have kept you away or that still keep you away? I’m curious.

PG: Great question. I think what I heard was that they understood… They didn’t use this language, but they understood that there was ghosts in the walls, they understood that the history that they had and what the media had called the theater of doom of 2016 and going out in the Euros to Iceland, and the amount of shame that went with that and the humiliation that went with that, they understood that that needed to be shaken out and that needed to be addressed at some level. So I heard them talk about a cultural context rather than just, “Well, we didn’t have the right guys on the team at that point.” I heard them talk about an understanding that the relationships weren’t solid enough yet between players, between staff and players, that Gareth, the coach, had only been in a year longer than me, or 18 months longer than me, which is still really new for a coach. And you get international teams, World Cup teams, and they don’t see each other very often. Everybody forgets that.

PG: It’s not like you’re in the locker room together every day. So what I heard was that they understood where some of the pain was, and they understood that it was pain and that it needed shaking out, but I also felt like they didn’t really understand how, but they were listening. So it was an arduous kind of process of interview over weeks and weeks and a two-day interview for the actual sort of assessment, and the more people I met, the more I kind of thought, “Okay, I can hear consistency in this, they understand that there’s like an essence of human relationships missing, and maybe an essence of the lack of identity as well.”

PG: What would I have heard that would have been a red flag? If I had heard bad apple, just one bad apple, or they’re not conforming enough. I really have a problem with more rules, that’s not the stuff that’s going to turn the dial where they need to fall in line. That wouldn’t have worked for me. That doesn’t work.

BB: No. The compliance approach.

PG: Yeah, and also I think the big deal clencher was that I felt like the coach was a humble and brave man. And there’s such a power pyramid in sports coaching, so the person at the top is overly glorified and so much depends on their character, and I felt like he was a kind person but humble and brave, and I felt like he could probably go on that journey.

BB: Wow, it’s so interesting. I want to just read something and then I want to read it as kind of a touch tone to walk through your book. Can I read from your book to you, is that okay?

PG: Please.

BB: And I just think it’s a beautiful moment that you and I are both big sports people, but not everyone listening is, but it’s a moment that I think captures something you can see at home with your children, you can see it at work, it’s a moment of clenching versus a moment of openness, and I want to use it just to kind of anchor us into the bigger discussion of your book. I felt it when I read it.

BB: So you said: I remember standing on the sideline at a big game. At a crunch point, I look to my right and noticed a colleague’s fist so tight, his knuckles were white, strain drawing his mouth into a hard line, no breath moving his chest. He was suffering, concluding it would go wrong before it had even happened. I looked to my left at another colleague, his hands were open on the metal railing in front of him, eyes focused but soft, his composed breath flowing in and out, almost smiling in appreciation of what he was witnessing. His trust in and empathy for the players was palpable. The reason for the difference? The second colleague accepted he was not in control, he was comfortable not being able to influence the moment; instead, he was able to surrender and accept it.

BB: Culturally, we think there always has to be tremendous striving and tireless work to succeed, so all the practice and training needed will be hard work in order to excel. We need to let go. This may sound flippant but you need to think like a Jedi, as Yoda says in Star Wars Three, Revenge of the Sith, “Do or do not, there is no try.”

PG: Yeah. Yeah, it resonates, doesn’t it? Because it’s the idea that if you let go of the striving in some way, then disaster is at the end of that. Our ability to surrender, I’ve heard you talk about sort of the death by rugged individualism, and that idea that we have to be sort of tireless strivers and in control at all times. And it’s just not reality. But even more than that, for me, it just steals all of the joy out of the endeavor when we can’t surrender to it, we can’t surrender to the idea that we have put in the blood, sweat and tears, and now it’s out of our control, and there’s something much bigger than us directing the traffic at this point, and just to enjoy what you have done, what you have created, and what is unfolding in front of you, without the need to control that something. When somebody really understands that kind of surrender, it is such a huge turning point for them as a performer.

BB: I interviewed Dr. Sarah Lewis on this podcast, and she’s a Professor at Harvard of Art History, also African American Studies, and she talks a lot about the importance of surrender, and it’s not giving in, but giving over too. And I thought about that when I read that. So let’s go all the way back to the beginning of Fear Less, which I want to make sure y’all understand I’m not saying Fearless. Pippa will help us understand why the book is not called Fearless, it’s called Fear Less, two words. Let’s go back to the beginning, and let’s talk about what you’ve identified, and I completely agree, are the two big fears that drive us in life.

PG: So the two big fears that are there for all of us at all times, it’s just a question of how much volume they have, are the fear of death, which you know we have, that’s really loud right now for us in the middle of the pandemic and what everybody has been going through over the last year or so, but the fear of death and the fear of abandonment are the two real, deep fears that we all have, and for me, that fear of abandonment in contemporary life shows up more as the fear of rejection, the fear of not being good enough in some way. And that’s the essence of the book. I talk about in the moment fear as kind of the organic, biological, natural warning light system that we have, the energy that is a response to a perceived threat, but then this much deeper, more pervasive fear of not being good enough, not worthy in some way, and how much control that has over us.

BB: How much in your experience working with CEOs, elite athletes, and teams, how much of what you see that’s getting in the way is driven by shame and the fear of not being good enough, loved enough, accepted enough. How much of it do you think is driven by shame and the fear of not being enough?

PG: Brené, I think most of it. I think most of it is driven by the fear of not being good enough and shame, and I think that we don’t hang around long enough with those uncomfortable feelings to really understand how much power they have, how much agency they have in our lives and how much space we give them at our table. They’re uncomfortable, they’re uneasy feelings, and we want to move away very quickly from them. But I personally feel that we have become way too obedient psychologically to these ideas of success that have culturally been bred into us. These ideas of success are narrow and conformist and they’re linear, and they generally just go upwards, not outwards or downwards into depth or width or groundedness.

PG: And I think that this idea that we’re just going to somehow get left behind, be shown up, be revealed as not quite all that, not quite good enough, is so pervasive in performers of all kind, that it’s stopped being humans performing, but humans have become performative.

BB: Wooh! Wooh, let me just take that in for a minute. That’s a hard swallow right there. Say that again.

PG: Yeah. Instead of human beings performing at the thing in front of them, their job, their life, their role as a parent, we have become performative, which means we don’t know how to not perform, where is the space in life where we’re not performing at something.

BB: When we’re not on.

PG: When we’re not on, but even when we’re not on, still, I feel that culturally, we are bombarded constantly with ideas of what performance needs to look like. Does your hair look right? Are you wearing the right thing? Are you connected in the right way? On social media, is your profile right? The smallest ways through to the grandest ways. I feel like we’ve kind of almost commoditized ourselves so much, that we don’t know how to not perform, we don’t have enough psychological space left at the end of the day to be not performing, not performative. And for me, that is an enormous drain on mental health, but it’s also a seriously lonely place to be, because how do you take your mask off, how do you show up as you, how do you find that deep authenticity if you constantly feel that nagging edge that you have to perform in some way.

BB: God, you know, what you’re talking about for me is hard, that’s like, I am having some hard swallows here, because I think that pressure culturally, especially when you’re in the public eye, like an athlete or a leader, or you or me, is so anxiety-producing for me, that not only… It’s so anxiety-producing sometimes for me that not only… And I don’t think you have to be in the public for this to be true, that the slow commodification of my life, I take on myself and perpetrate it against myself, sometimes, it’s not just outward, it’s a learned behavior. And I think, tell me if you agree with this or disagree, let’s rumble about it a little bit, I think I’ve gone into cultures, high performance cultures, not just sports teams, but also organizations, where they actually try to leverage that, like they think that’s the right way to get the maximum out of people. Have you seen that?

PG: In most teams I’ve worked in, there is an element of that, that’s exactly one of those things I want to shake out when I’m in an organization or a C-suite or a team, this idea that fear, that sort of performative fear is some kind of good motivator, right? Fear of not being good enough, fear of not performing at your best is, let’s be realistic, that has some advantages to performance, it might keep you focused, it might drive your effort, but it has many more downsides. When you’re actually in an anxiety state, it’s harder, it’s harder even physiologically to be fully clearly here and present. It is harder to stay focused, it is harder to have clear conviction and stick with it and even find courage when anxiety is kicking around in the background.

PG: So I think it’s a lazy tool for motivation to constantly expect performance from somebody, and I think we hero it too much. I would love it, I would love to think that in general culture, let alone sport, that we can heal some of that over time, because there’s too much cost, you pay too much mental rent to be a performer at all times, whether you’re at the school gates picking up your kid, worrying about what the other parents might think if you’re 10 minutes late, or whether you’re walking out on stage to give a huge presentation or you’re about to swim a 100-meter race in an Olympics, it’s the same staff, actually, it’s the same how am I showing up as a performer? And I just think it robs us of the richness of life, I think it’s a thief. If we don’t know how to right-size it, if we don’t know how to turn it down, and if there isn’t some psychological space at the end of the day, where you are just Brené and I’m just Pip, and that’s it.

BB: Yeah, and I think we’ve got so much testimony to that. Not only do we have so many athletes and performers telling us the truth of what you’re saying, the metrics by any measurement are better when people don’t have what they produce tied to their self-worth. You cannot, you cannot come back from that. The first time you get picked off or the first time you mess up a race or the first time you throw an interception, you can’t come back from that. It is so antithetical to resilience, do you not think?

PG: Totally. Your results are just an outcome. That’s hard to swallow, right, because your results are just an outcome, they are not your worth.

BB: That’s a big sentence for people.

PG: Yeah, it’s really a hard thing to face into, but I think when we do, there is so much freedom that comes alongside it. There’s a story in the book with Lee Spencer, the rower…

BB: Yeah, tell us.

PG: Lee Spencer’s an unbelievable human being. The first time I introduce him in the book, I’m telling the story of him as a dreamer, the power of dreams and desires, and he just wanted to be a Royal Marine for his whole life, and he tells a story of being knocked back and you’re not good enough, you’re not the captain of anything, you’re not really our kind, kind of thing, and how much it fueled his desire and how much he just had a dream that was bigger than all of it. And I introduced him in this way in the book, but Lee’s story is phenomenal, because after… He got into the Marines and he did three tours of Afghanistan. And when he had finished that and he was home on a break one Christmas, I believe it was a Christmas break, he was involved in an accident. He had stopped to help some people on the roadside and it was dark, and another car crashed into the car that was stopped, and an engine block flew out of the car and severed his leg, totally dislocated one leg and severed the other below the knee.

PG: And he had to make a decision, talk about courage, he had to make a decision at that point whether he was going to call his wife and say goodbye, or whether he was going to choose to live. And he chose to live, and he found in himself such a desire to have quality of life again, and that led to him doing two Atlantic rows, one solo, one with a team. And I tell the story of him dealing with fear, first in-the-moment fear, facing down 40-50 foot waves and kind of trying to make a decision as to whether to cut his rope, because he was going to get tangled and he was going to go down, and how he dealt with that. But also then this, his sense of worth as a person who now was rowing the Atlantic with one leg, how was that tied to his sense of himself having a disability.

PG: And he tells this gorgeous story about halfway through the row he kind of recognized that, oh, I’m the same guy I always was. My circumstances have changed, but at the end of the day, I’m still Lee and I’m still worth everything I was ever worth. And he talks about having a kind of an epiphany in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where he realized that he wasn’t a label, and he realized that nothing that he needed to do in a performance was ever going to make a difference to his worth. And it’s just such a beautiful description of him recognizing that his worth was not tied to that world record. I mean, he knocked 36 days of the able-bodied record, right, it was an incredible performance, but he recognized half-way across the ocean that that wasn’t his worth.

PG: He didn’t have anything to prove in terms of who he was as a human being, and he didn’t have to be defined by that. I just find that story so moving because…

BB: It’s beautiful.

PG: Yeah. And he’s the most straightforward, humble Englishman, and you just read about people like him or talk to people like him, and you learn so much about courage, but also about genuinely where you find your worth.

BB: This reminds me of another story in the book that I would love for you to tell about the difference between deep wins and shallow wins. Can you tell that story, because it really stopped me in my tracks and made me think about a lot of things. I’ll give you this precursor. It made me think back again to Sarah Lewis’ interview that we did about the pursuit of success versus the pursuit of mastery, and it also made me think of Simon Sinek’s work around the Finite Game and the Infinite Game, and how Simon doesn’t really subscribe to this winner/loser paradigm. I never thought about a deep win versus a shallow win, because, I’ll be really honest with you, I’ve only had a couple of pretty serious bouts with depression, but one of them was around tying my self-worth to getting into a PhD program.

BB: And when I got in, it didn’t fix anything, and it was a very shallow win, and it turned into three months of not being really able to get out of bed. I had a Post-it note that would say “Get up, unbutton your pajamas,” it was a very shallow win and I was tying the wrong things together. Going back, I guess I was like you, I didn’t come from a long line of academics, it wasn’t my destiny to get a PhD and become a social scientist. I also come from addiction and hard stuff, and I love social science, so it was confusing because I wanted it, but I pinned the wrong things to it, and it was so shallow in the end. So tell us about that concept, tell me what was going on there. Pippa Grange me.

PG: Yeah, I’m grateful for you sharing that, because it’s the perfect example. I describe the difference between winning shallow and winning deep as really being about that, the ability to separate it from the fear of not being good enough. So when I was over 20 years of work in the field, maybe about 10 years ago, actually, I started really noticing some patterns in the people that I was working with, and what I noticed was that some people who were really exceptional performers in business and in sport, world record holders, absolutely at the top of their game, everybody else’s idea of a successful hero, they would achieve something, and within a day of that achievement, the scarcity mentality would creep in again, the idea that, okay, what is next? Urgency and scarcity were just right around the corner at all times.

PG: And what I noticed was that some people would win and feel their win, enjoy their win. Some people could fail and have enjoyed the endeavor, but many, many high achievers, and I mean a lot of high achievers that I worked with, they basically couldn’t feel their success, they couldn’t enjoy it for a second, because straightaway they were into the next thing. So winning shallow for me is about winning to avoid not being good enough, winning to beat the other guy, winning to be seen as good enough, chasing it and not having that sense of rich fulfillment. We’ve all been there, we recognize this stuff. That’s winning shallow. All the trophies in the cabinet, all the accolades on the CV, the drum roll of who somebody is, none of it, none of it is actually tied to your worth.

PG: And as soon as we do, then we open the door to that not good enough fear. So winning deep for me is where you actually can feel the richness of your journey, you are attached to the joy and the struggle, you are attached to the mess, and it is generally done for reasons outside of yourself and the fulfillment of our egoic needs is done more from a soul level, it’s done because we can, and because there’s a wild desire in it, something much less domesticated in it. That’s winning deep. And sometimes our deep wins are not big things, it doesn’t have to be a World Cup, but when we win shallow, we feel urgency, scarcity, self-doubt, nagging at our ideas of worth, and we never really truly, wholeheartedly believe that we are enough. That’s winning shallow.

PG: And I also think we can generally see a whole heap of need to dominate the other when it’s winning shallow, because it’s comparative. Winning shallow is comparative.

BB: It’s so comparative.

PG: Yeah, and we’re never going to feel that fulfillment in that, you might feel a thrill, you might have enjoyed it, but it’s different to a soulful, deep joy in having achieved something. You might not just achieve it, you have to feel your achievements. That’s a really big difference. And beautiful Paul, the story I tell of Paul was an athlete that I worked with, who he had had a dream of playing football since he could pull on his own socks as a kid, and it was his thing with his granddad, and they were very close, and he just always wanted to play professionally. And when he was playing out on the streets as a kid and he had that sort of deep love and really loved the game, he was playing, he was free, he was showing his talent in its raw form. The story of Paul is he moved into that professional environment and it became more commoditized.

PG: It wasn’t just that it became more structured, that’s necessary, or disciplined, it wasn’t all of that, he was prepared for the hard work, but he wasn’t prepared for the meanness that he experienced or the dismissal or the narrowing of his joy. For him, football was love, and he just got the love squeezed out of it by a particularly dismissive, mean coach who had no care for him as a person, he saw him as an asset or a resource. So eventually he just lost all the love, and eventually they did win a trophy, the trophy that he’d dreamed about from being five years old, and he remembers holding it up in the locker room afterwards and feeling just empty. That it was a vapid win. There was a statement on the wall in the locker room that said “There’s no finish line,” and he was thinking to himself, “I wish there was.” Even as he was holding the trophy, because there was no love in it anymore.

PG: And we move into an ego zone because everybody else thinks you’re living the dream if you’re that athlete or if you’re Brené Brown, if you’re that one person who everybody else looks to, everybody else has an impression of it. But the important thing is, can you feel it as well as do it. And he lost it.

BB: Yeah, he lost it. I obviously do and have done a lot of my own work, and for me, I know when I trip that wire it’s very clear for me, because I trip that wire when I have to be the knower not the learner. And so for me, the joy in being a social scientist, the joy in being a researcher for me is my insatiable curiosity and learning, and so the moment I buy into this external belief that I have to have the answers, and I let myself slip into the knower, all the joy of my job comes out for me. I still can slip, for sure, but the minute I have to be right and can’t just enjoy the pursuit of trying to learn and get it right, all the love goes away, that just becomes grueling, like walking on glass. I don’t think it’s too strong to say I hate it, I resent what I love. Is that weird?

PG: Yeah, no, I totally hear you. I empathize with that a lot, it’s like the terror of being the expert. I can’t think of an expert where I also think love. I can think of people who are really appealing and I want to learn from them, I want to hear them, I can’t wait for their next installment in some way, but they don’t play expert, because as soon as the expertise comes in, there’s something hardens or becomes colder. Because it’s too muscular, it’s too cold, and there’s no room for love in there, so stick with the curiosity, that’s what you do, that’s what I do, and I think that that’s where courage comes in. It’s like, can I do what I think is right rather than what other people might expect of me, because the reward that they’re looking for will come from you doing that anyway, right?

BB: That’s right. I have to say that as I’ve been thinking about this a lot, I’ve had conversations with other people, I just did this incredible interview with Dr. Yaba Blay for Unlocking Us, and I just have to say that the academy does not train us well to be vulnerable, soulful, love-centered learners. Do you agree?

PG: I totally agree. I think some schools have got better at this, but many of the theaters of our learning teach us to be invulnerable by never being wrong. I have a friend who’s a surgeon, who was a surgeon, and I was talking to him the other day and he was telling me that that culture among the surgeons that he worked with eventually drove him out of the profession, because it was so egoic and so much about power, that the ability to be vulnerable, to show strain, to get something wrong, and clearly, I’m not talking about within a surgery, but just in being…

BB: And as a human, yeah.

PG: It wasn’t tolerated, and I think academies of all kinds teach us that that’s not an acceptable level of performance and what a loss, what a loss, because that is not a way to live, that is an exhausting way to live and an enormous strain on our mental well-being as well, to constantly be acting as if you always get it.

BB: And as someone who’s located in the largest medical center in the world, Houston, and I do a lot of work with grand rounds, and medical schools and residencies and fellowships, and what I can also say is it also drives unnecessary death and illness, because the culture of shame that permeates surgery and other medical cultures drives covering mistakes. What people I think don’t understand, and I think this is sometimes true on professional sports teams, the shame is not always about how am I perceived by the fan or in medical culture, how am I perceived by the patient or their family, the greatest shame is often how am I perceived by my colleagues, my peers. And so rather than openly talking about learnings and mistakes and growth, that stuff is covered up. We cover up injury, we cover up mistakes, we cover up illness, and there are real consequences to that, I think.

PG: Absolutely. And again, the metaphor of the sports team is perfect here. The thing about sports is it’s like a microcosm of life that’s really visible week to week and the results are really obvious week to week. But if you can’t acknowledge what isn’t going right you can’t change it, you can’t improve it, if shame is in the room, you can’t take the risk you need to go try something else, to go experiment, right? Because when we’re experimenting, we’re learning, and most of the time we fail, right?

BB: We’re failing, yeah.

PG: As I say in the book, even the arithmetic doesn’t work on this idea of never getting things wrong. It’s such a crazy ideal to presume that there would be a no mistake culture. The strain of that, the strain of holding that is profound for people. I see that at all levels of society, the strain of being what other people think you are and then acting according to that impression, managing your impression to suit the label or the false ideal somebody else holds you to. I make mistakes, 50 million a day, and some are more important mistakes than others, and you try and correct them, but that’s a quick drift into perfectionism, and that is a quick slide as well into an egoic way of life that doesn’t allow you to feel, because you just can’t. If you’re constantly watching your back for whether somebody else is going to criticize, shame you…

BB: Blame you.

PG: Denounce you publicly, let somebody know that you weren’t enough in that moment. If that is where your attention is, then all you will do is stick with the familiar, stick with the tribe that you know, reduce your curiosity and live in a vigilant state, and that can’t be it. That can’t be it.

BB: I love this quote. There’s two quotes I want to talk to you about from the book that I just loved, and then I want to ask you some questions about your new endeavor, because I want to know more about it and I’ve got a couple of questions. This first quote: It is scary to talk about soul or love in our hyper-rational data-driven world, but I am convinced these are the missing pieces in our potential. And in fighting fear, this is the only genuine way to talk about change and becoming fearless.

BB: So I want to tell you about my experience hanging out for a day or two with the Richmond Tigers. They had been Pippa Granged up full on, like these folks were living and breathing your work, right. And they had read my work and they were familiar with my work, and for those of you who do not know, Australian football, it’s like soccer meets rugby meets American football meets Quidditch. I don’t know how else to describe it.

PG: That’s perfect. Perfect.

BB: Yeah, it’s crazy and it’s hard and it looks dangerous, and I think they run something like 12 miles a game because it’s… And they’re young. You don’t see folks into their 40s, usually, these are young kids, right, 18, maybe, to 25, 30.

PG: They’re drafted at 18. Some guys make it to the sort of early 30s, but yeah, it’s a young person’s game for the men and the women now.

BB: For the women and the men, yeah. So I’m there and I catch glimpses of them interacting with each other. First of all, I get there and a couple of them say “Hi,” and the others are kind of standoffish, and the captain comes up to me and says, “They’re so scared to meet you.” And I was like, “Why?” And they’re like, “We’ve all read The Gifts of Imperfection, and we cried every time we talked about it,” and I was like, “Where am I?” And I heard them say “I love you” to each other, and again, I’m getting teary, I wasn’t expecting this during this conversation…

PG: They make you cry, the Tigers.

BB: Yeah, they make me cry, and I had my at the time 12-year-old son with me who’s an athlete.

PG: Great model, yeah.

BB: Yeah. And they walked me through in the locker room in their, I don’t know what you call it, their building…

PG: Their club rooms.

BB: Their club rooms, yeah. They had art that they had all done hanging, I was like, “I’ve got to meet this person.” And it’s never just a person, because there were so many people there, but there was something different about that club, and the fact that they have been on the successful tear through the AFL and just performing does not surprise me at all. These people love each other. Tell me about love and soulfulness.

PG: Yeah, I’m so pleased we’re talking about this, because the Richmond Tigers have won three premierships back-to-back. That is extraordinarily hard to do. And I think that they’re just a testament…

BB: Is it?

PG: Yeah, really…

BB: Is it rare?

PG: Yeah, it’s rare. And it’s just testament to the fact that you don’t have to choose between being whole-hearted, loving, kind, soulful, or winning, you can do both, but the bridge you’ve got to cross is vulnerability, and they cross that bridge.

BB: Oh, my God. That’s going to be a quote on something. That’s going to be a quote, y’all prepare for that quote to be somewhere. Okay. That bridge is vulnerability.

PG: Yeah, and that’s a long journey they’ve been on, so Brendon Gale, their CEO, and they have the first female president, Peggy, I hope you met Peggy, she’s just the most wonderful woman, and Shane McCurry, who was the guy you were talking about before, yeah, he’s divine. And they had been on a long journey with Damien Hardwick and Trent Cotchin, the coach and the captain. When I was working with them, we did something called a deep end journey, and I took a group of Richmond players, indigenous and non-indigenous, to Rio, or I did this with a group called Global Reconciliation, and we went to Rio and we looked at how sport can be used as a vehicle for reconciliation and for deep identity.

PG: And we started right back there talking about who we were and identity and what sport is. It’s not just a scoreboard, it’s not just a trophy, but I love their story so much because it’s filled with soul, and they have three premiership cups alongside that, so they’re the perfect example for me that you don’t have to choose, you just have to be willing to do it differently. And that’s why they’re in the book and their Triple H exercise that actually came from Mike Smith, I think, from Atlanta Falcons originally, and Shane ran Triple H with them, to stand up in the front of the room and tell a story of a hero, hardship, and highlight in your life.

PG: And in the book, I tell the story of like they were absolutely shaking in their boots terrified of doing this, but having done it, somebody sees the whole you, you drop performative, you drop it, you have to shed it, and when you do that, guess what? You’re still loved. And the strength of that and this idea in sport of like playing for each other, how do you play for each other if you don’t know each other?

BB: Don’t know each other, yes, if you don’t see each other and…

PG: Yeah. And that just stays in the performance realm, and we’ve got to go beyond that. It’s the same in the stories of Scotty Mills that’s in the book, the story of him in the Royal Marines and his relationship with Lee Spencer and how do you connect heart and soul with another human being. And I talk about Richmond as intimacy. So one of the gateways to soul is intimacy. I think it’s unfortunate that we’ve kind of narrowed that down, that term, we’ve narrowed that down as if it was just something in the sexual realm or something that happens just within families and within loving relationships as couples. Intimacy is critical for all of us, because if I can be intimate with you in this conversation and I can look you in the eye and show up just as me, and this is it, we’re being intimate. That is a gateway for soul, that means that that soul can show up.

BB: That’s beautiful.

PG: And when it shows up, then game on, everything is possible. And I just think we can take so many more risks, we can go much closer to the edge of what we’re capable of, we can imagine in ways that we couldn’t possibly imagine before, and we can let soul in. And that’s where for me, the deep winning is.

BB: Yes, and it is not only the fire of life, it’s so funny to me how people think that soul may be the fire of life, that it distinguishes the fire of performance, but what you said they have to cross the bridge of vulnerability, and that’s where people defend their own comfort before they protect their team, right?

PG: Yeah, well, you defend your own comfort if you think that stepping outside of that comfort will be a bruise to your worth, if that will reveal you are not good enough, because sometimes in sport or in life, we’re just not actually good enough on the day performance-wise, that’s a reality, but it’s not the same as not good enough in your soul, in your work. That’s the distinction we have to make. It takes quite a lot for people to genuinely turn and face that. When I start talking about soul… Well, when I go into an organization, I don’t talk about soul, because you have to build some trust first.

BB: Oh, for sure.

PG: I have felt I had to build some trust first, otherwise, it’s kind of like, who’s this crazy with the tie-dyed shirt playing the flute under a tree talking about soul. You need to be winning here. And it’s too far away, you have to find ways to meet in the middle, and that meeting in the middle is through trust and through understanding, “What do you need? Here’s what else I think you might need to get there,” and then how much richer would it be if we did it this way.

BB: Amen.

PG: So I think there’s a lot of meeting in the middle.

BB: Yeah. I mean, I think that’s… For me, I’m a social worker, and our ethic is we start where people are.

PG: Right. It’s the same with psychology.

BB: Yeah, then you have to walk them based on where they want to go. Let me ask, this quote, I just love this, from Fear Less: Trusting in something bigger than you is one kind of useful surrender, but there’s another kind of surrender that’s useful against fear: Letting go of control. Ouch.

PG: Yeah. Again, this links so much to the idea of us as mechanical robotic performers. If you can surrender that and let go of the idea that you’re in control of the outcome and all the mystery is squashed out of life or out of your results or your achievements or your success, all mystery is gone because you have controlled the minutiae, you know everything that’s coming at you. If you can’t surrender, you can’t allow mystery, and if you can’t allow any mystery, you can’t open the door to soul.

BB: It’s very hard, not just for me personally, but with the folks I’ve worked with, the leaders, especially the coaches, it’s very hard to let go of control when I have my self-worth tied to the outcome. Is that true in your experience?

PG: 100%. And I think that it’s a worthy exercise to map out what you actually need to control and where your ego has joined the party. And your ego and your fear of being revealed as not expert, not knowing enough, not getting it right, having made the wrong choice about something, where that fear comes in, and what are you controlling for. So if you’re controlling for process, if you’re controlling for executing the system that you want to play, or if we’re talking about a realm outside of sport, if you’re controlling for the way that something gets done, that’s fine. If the guys with their clenched fists on the metal rail that we talked about earlier, if you’re controlling for the actual outcome beyond all the things that you did to create the possibility of an outcome, then you’re in ego land, and that’s where your worth gets tied to it, that’s where your idea of being shown up as not good enough gets tied to it.

PG: You can’t control the actual outcome, you can control loads of things on the way up, and then you’ve got to let go. And if you can’t let go of that, well, for a start off, you can’t breathe, but you can’t allow for all of the mystery that we were talking about before, all of the soul, all of the possibility, all of the play, all of the love to take us to a place that we weren’t expecting. You can’t leave room for anything unexpected if all you can do is control, so you’ve got to surrender that.

BB: Do you mind if I read one more story to you…

PG: Sure, go ahead.

BB: From your book. There’s a story from your book that I think about a lot, and I’m not a musician at all, but this story has… Do you know that story I’m going to tell?

PG: Yeah, I love her.

BB: This is an incredible story: A young musician, a trumpet player, contacted me after the 2018 World Cup and asked if she could come and talk to me about ways to deal with her performance fear. A rising star in a field where discipline and perfection are revered, she felt she had lost her confidence in big performances under her fear of making mistakes. We went through the basics of her emotional management and pre-performance routines, techniques similar to those in Chapter 8. So one thing I love about your book, Pippa, is that you’ve got very specific strategies, ideas and techniques, like you’re just generously sharing everything that you have done and learned, so grateful.

BB: So you go on to say: We talked about how she could stay composed in the time leading up to her taking her seat in the orchestra, but something still did not feel right. I asked her to tell me what the music felt like. “Feels like?” she said. “Well, I kind of hear it rather than feel it, but I guess my mouth feels the vibration of my lips inside the trumpet mouthpiece, and I guess my fingers feel it, the pressure between my finger tips and the tops of the valves. Actually, I guess my ears feel it too, the pitch and the tone of a good note or a bad one. Well, now that you mention it, my whole body feels it. I can feel space in my back ribs, and the rise and fall of my stomach as I breathe, I can feel my legs and arms taut and engaged, and I can feel the resonance of all the other sounds of the orchestra through my feet on the floor.”

BB: And then you, Pippa, turn to her and say, “So how does music get made? Do you make it or does the trumpet make it?” She considered this for some time. Her answer: “We make it together, it comes through me, but the music already exists, it just needs me to breathe and enable it to come to life.” So then Pippa says, “So the more open you are, the easier it is for you to pass the music into the trumpet,” I asked. “So you can create together.” She responds, “Yes. Yeah, that’s 100% right. It always flows best when I’m open and I hadn’t really considered it as creating together until now.” So the onus for perfection can’t really be all on you, you say, Pippa, and your ability to execute the music, it sounds more like your job is to stay open.

PG: Yeah.

BB: Damn.

PG: Yeah. She is amazing, she is an amazing performer, and the next piece in that story is her recognizing as well that I ask her what she wants her audience to feel, and she says she wants her audience to feel filled with emotion, and she wants them to feel joy. And so I talked to her about, well, not only do you need to stay open, but do you need to engage them in the creation as well? And she say, yes, they’re part of the creation. So suddenly, when she comes into the orchestra and she comes into that amphitheater of creativity and sound, she’s not worried about her own perfectionism and whether there’s a dud note coming, she is thinking about creating with these hundreds of people in front of her and her beautiful instrument, she’s thinking about creativity and openness and flow, not about what she’s doing, she’s just one snippet of that wonderful creation. And straightaway her attention’s in a different place.

BB: God, it’s beautiful. I use that, I use that all the time. I don’t play the trumpet by any means, but I do create things with other people, and my job is not to hold on so tight that I squeeze the life out of it, but to stay open and breathe and co-create in every moment. We’re co-creating right now, right?

PG: Yeah, and that’s why the idea of the expert is so flawed. The attachment to the idea of expertise and never getting something wrong as the expert that how can you co-create if all the expertise is in you. You have gifts that you want to share, but they’ll come through the expression with others, they manifest in the expression of conversation. The various ways that you do that. It’s always co-creation. It always co-emerges.

BB: Okay, tell me about what you’re doing now, tell me about the organization you’re working with, because I have a question about it, so tell us what it is, tell us where you’re working right now, and you said that something’s coming soon in Egypt as well. So walk us through what you’re doing now.

PG: I work for an organization called Right to Dream, and as I said before, it’s a football organization, but really it’s an ecosystem of opportunities for young people from… We have two African academies, one in Ghana and one coming in Egypt, and we have a football club in Denmark, and we will have more academies and more football clubs, and it is an ecosystem of opportunities for boys and girls from as young as 8 to come through and have an education, an academic education, a football education, and then education in character and purpose. So we want to help grow socially-focused, purpose-oriented athletes who see themselves as more than the scoreboard and who want to give back into the world beyond their own window as they grow as athletes.

PG: And it’s been an immensely successful endeavor so far for something that started on a dust pitch in Accra with Tom Vernon as a sort of 20-year-old guy and no idea what he was doing, basically. He moved 10 kids into his house with his then girlfriend, now wife, Helen, and they’ve had an extraordinary journey where they have many children, many young people have gone through American universities and achieved extraordinary things, and many have played professional football and played for their country, and they’ve all come out with really good character as well. So our endeavor now is an expansion of that ecosystem into different places, we hope to come to the US, we’ll come to the UK at some point.

PG: And we really are about changing the way football gets done and focusing on the humanity in the middle of it, rocking the boat a little bit about some of the ways that academies work, youth academies work with, it’s not too strong to say, a disposability mindset around young people and young talents, opening the door much more for girls, African girls, but girls all over the world to achieve their own dreams through sport. And yeah, we’re really kind of on a huge mission now to redefine excellence, so it’s got a whole-hearted living right in the center of it, and it’s way beyond the scoreboard.

BB: It’s beautiful.

PG: I feel very, very thrilled to finally have found kind of kindred spirits in that endeavor, and I’m excited for what comes next with them.

BB: God, and to bring all your expertise and your experiences, what a match made in football heaven, this is good. Here’s my question for you, as you think about Ghana, Egypt, Scandinavia, what needs cultural translation in your experience so far, in terms of whole-heartedness and vulnerability and courage and authenticity and perfectionism, what have you found that is kind of universal, and what kind of cultural translations are you finding necessary if any?

PG: The cultural translations are for us going to Ghana. The kids and the Ghanaian people that I have encountered and all of our students in the academy, they already get vulnerability, they already get resilience, they already understand connectivity and intimacy and whole-heartedness. They teach us. We had a situation where we had some commercial partners go down to the academy last year, and they had been sponsoring the organization for a while in a particular area of the academy, and I remember one of the very senior people in that team being kind of shocked when a 13-year-old girl had said, over lunch in the big dining hall, so what’s your purpose? What are you doing for other people and the world around you? And this guy was super successful, going, okay, wow, I need to re-check on what my priorities are. And he was very moved by that. So they teach… In terms of that cultural translation, it’s this way, they’re teaching us.

BB: Yes, so y’all come in as learners and they’re knowers of their own culture.

PG: Yeah, right. We’re coming in as learners and it co-emerges.

BB: Beautiful.

PG: I think so many of those ideas we have about Africa and the African continent particularly has been that somebody needs saving or teaching, but that is not my experience, it’s not Right to Dream’s experience, the talent is there, it’s just the opportunities that are missing. And their culture is rich in everything that we care about, so I feel very blessed to learn from them.

BB: If you were going to make up where the story is at this point in your career, you could not make up something more perfect, right? Yeah, and then starting with our kids… It’s incredible. Thank you for doing that work. We need it so desperately. And those academies, you talk to players that play professionally, and there is a discard disposable fight, someone else is waiting for that jersey and that opportunity, and you’d better stay grateful and scared all the time. Do you know what I mean?

PG: Totally. And if you’re being picked up in a limo at age 9 and you think that this is it, you have arrived. If everybody around you in your peer group age and your family feel that you’re a hero, you are terrified about the expectation and about giving that up or losing that up, and when you’re dropped off nine months later in an Uber and you didn’t make it and you’re a failure by the time you’re 10, that is not okay. And there are different ways for us to assess talent and to let people transition who aren’t going to have the physical talent or skill, there are different ways, that is not good enough, and we have to change some of those attitudes in sport.

BB: Amen. Alright, Pippa, are you ready for the rapid fire?

PG: Yeah, I only have prepared on the rapid fire my five songs. Is there more?

BB: Yes, there’s eight questions before or seven questions before, so we don’t want you to prepare for those. Are you ready?

PG: Okay, cool. Yeah, I’m ready.

BB: I have a feeling you were born prepared for these. Okay, number 1. Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

PG: Vulnerability is a tricky gift, like a gift you would not have chosen for yourself, but it turns out to be super valuable and something you really needed.

BB: Number 2, something people often get wrong about you.

PG: That I am extroverted and confident.

BB: One piece of leadership advice that’s so good you need to share it with us or so shitty you need to warn us. I feel like that’s your whole book.

PG: Yeah, that’s the whole book. But I think create the space for you to really understand your own mind and your own convictions, because if you don’t know them, you will fall for too much of the fear.

BB: What is the hard learning that the universe just keeps putting in front of you over and over that you have to re-learn and re-learn and re-learn.

PG: For me, that is that I can really trust men. That hasn’t been an easy journey for me. But I keep meeting some really fantastic ones and the universe keeps putting them in my path and saying just the same thing, you can trust, you can connect. You don’t have to have your guard up around men.

BB: Powerful. What’s one thing you’re really excited about right now?

PG: Right to Dream and the possibilities of this huge journey we’re about to go on.

BB: Tell me one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now.

PG: I am deeply grateful for Ablaye, my husband, who is genuinely a fear less kind of guy and who has his feet on the ground, and has the kindest, most loving heart that you could possibly ever know, and I’m so grateful every day for him.

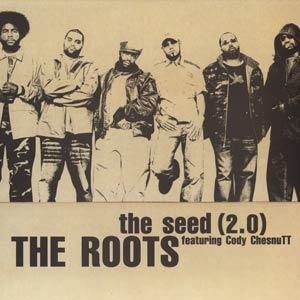

BB: Okay. We asked you for five songs you couldn’t live without, and we made a mini-mix tape on Spotify of these songs. Let me go through them with you. “Redemption Song,” by Bob Marley and the Wailers. “Ain’t No Sunshine,: Bill Withers. “Hallelujah,” the Jeff Buckley version. “Feeling Good,” by Nina Simone, and “The Seed,” by The Roots. In one sentence, what does this mix tape say about Dr. Pippa Grange?

PG: Soulful.

BB: I could listen to music with you for a long time.

PG: Yeah. I just refuse to believe that anybody can listen to those five tunes and not just shift their mood, shift gear, feel it in their bones, they are like, wow, that kind of soulful music is just like, oh, I love it.

BB: I love it too. I have your mix tape on repeat on my Spotify. It’s so good. Pippa, thank you so much for just sharing yourself, your story, your wisdom, your insights, your hard-fought learnings, thank you for sharing with us on Dare to Lead. I really am grateful.

PG: I’m so grateful too, and I hope that something rich co-emerged and was created in the conversation for your listeners, and I really hope we get to do it again sometime.

BB: I would love that. I cannot wait until when we can travel again. The next time I’m in the UK, I would love to… Maybe we can meet for a Richmond Tigers game sometime.

PG: Definitely a Tigers game. But you should come down to Ghana, you should come to the academy. That would be amazing. Yeah, come.

BB: Y’all heard it here, I’m taking that as an official invitation.

PG: It’s an official invitation.

BB: I would love that.

PG: You would love it, yeah, for sure. You must do it. I’ll hold you to it.

BB: Yes, you can. Thank you, Pippa.

PG: Thank you Brené.

BB: Alright, raise your hand if you love Pippa Grange. I learned so much from this conversation, I love it. I mean, who gets a job where you finish school, you graduate and your job is just to keep learning. This is the best thing in my life. You can find Fear Less: How to Win at Life Without Losing Yourself wherever you like to buy books. Big heart shout-out to our indy bookstores. We’ll also put a link to it on our episode page. Pippa is pippagrange on Instagram, and the website is www.righttodream.com. I’ll also be going to Ghana to visit this academy, which I cannot wait until we know when I can do that, so I can put it in my planner.

BB: The Dare to Lead podcast has an episode page for every episode on brenebrown.com. All the links, transcripts, a link to the mix tape, which man, her music was so spot on, so good. You can also sign up for our newsletter there. Thank you for listening to both Dare to Lead and Unlocking Us on Spotify. I’m super grateful. Let’s keep learning together. Awkward, brave, and kind, friends, I’ll see y’all next time.

BB: The Dare to Lead podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and by Weird Lucy productions. Sound design is by Kristen Acevedo and Andy Waits, and the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.