Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

BB: In today’s episode, I’m talking to my friend, Dr. Scott Sonenshein, about his book, Stretch. We read this book across our organization last year, and it turned our thinking upside down. So, today we’re going to dig into what it means to be stretchy, what it means to be chasey. We’re going to talk about parenting, we’re going to talk about work, and we’re going to talk about that gremlin that is problematic for all of us, I think, especially right now. It seems worse during COVID. Comparison. So, Dr. Scott Sonenshein, his new name is going to be Dr. Scott Walking-On-Sonenshein, you’ll see why later in the podcast. It’s going to be great.

BB: So, Dr. Scott Sonenshein is the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor of Management at Rice University and is a New York Times bestselling author whose books have been translated into nearly 20 languages. In addition to Stretch, he also has co-written a book with our friend, Marie Kondo, called Joy at Work. So he’s got these two books; he’s written for, I mean, every outlet you can imagine: New York Times, Time Magazine, Fast Company, Harvard Business Review.

BB: He holds a PhD in Organizational Behavior from the University of Michigan. He has a Master’s in Philosophy from the University of Cambridge and a bachelor’s from University of Virginia. That’s a ton of schooling. Just imagine the school loans on that sucker. Woo. His research appears in the very top academic journals, and he’s contributed to several topics in management and psychology, including change, creativity, personal growth, social issues, decision-making, and influence. He’s just a fascinating researcher, a really good guy, and my sometimes walking partner here in the cool, crisp days of Houston summer. Let’s meet Scott. Okay. Welcome to Unlocking Us, Scott Sonenshein.

Scott Sonenshein: Well, thanks again for having me on.

BB: I am so excited. You know how much I love Stretch. This book has been a game-changer for me, and for all of us at our organization. It’s like mandatory reading over here.

SS: Yeah, no, it’s exciting to talk to you about these ideas, especially the situation that we’re in in the midst of a pandemic. And I think it’s a time for all of us to think about how being resourceful is something we can use to not just cope and get by but to even maybe thrive during these circumstances.

BB: Yeah, I think as I was re-reading it in preparation for the interview, I really thought to myself, we need this now, and, boy, do our kids need these lessons right now.

SS: Yeah, I’ve got… I’ve got two daughters at home, 8 and 13 now, and they’ve been home since March, and you run out of things to do after a while, and it really challenges us as parents, and them as children, to think about how they’re going to go about their days and their lives, in dealing with so many of the challenges that we have right now: uncertainty, when this is going to end, what’s going on with the pandemic. Relationships, they haven’t had real play dates and connecting with their friends in months. And then, of course, as parents, we’re also trying to work, and sometimes that’s hard when we’re also a camp counselor, a homeschool teacher, entertainer extraordinaire. And it really provokes having to change our mindset into thinking about, “Well, how can we actually turn this into some teachable moments and opportunities, and deal with trying to do many different things at a time? And I know that sounds a bit intimidating, but I do think there are some simple things we can do to change our mindset that can actually turn these circumstances, none of which we wish that we’re in, but into an experience where we can build connections, bond with our children a little more, and teach them something.

BB: I love that. So Stretch is basically… I categorize it, which you may disagree, so tell me, is basically, in my heart and mind, a book about resourcefulness and scrappiness. Tell me about the path that led you to Stretch. Tell me about your life and how you ended up writing this book.

SS: So, we’ve got to go back a couple of decades, and I had just graduated college and I was working for a strategy consulting firm in Washington DC, and I got a phone call pretty much out of the blue from a recruiter, this is during the internet boom, and she said to me, “We’ve got a great job for you in Silicon Valley. Come leave everything in your life to come out and work for us, and we’re going to give you a raise, we’ll double your salary, we’ll give you a million-dollar budget to manage, we’re going to give you a team to manage.” And I was like a year out of school, and I was like, “Okay, this sounds amazing. Of course I’m going to sign up for this.” I had never been to the Bay area, so I went out there, and they told me about all these wonderful things they were going to do, and how we were going to change the world, and everyone was going to get super-rich. And I signed up. And three weeks later, I moved my whole life out there. And for the first few months, it was… It was exhilarating in many respects because it was almost like the money would not stop flowing. Venture capitalists were throwing tens and tens of millions of dollars at my company, and so many others. And there was a really simple but kind of eerie formula for what success was out there.

SS: It was people give you money, you spend that money as fast as you can, and magically, they’ll give you more money. And everything becomes worth more, on paper, at least, of course, until things came crashing during the… The NASDAQ stock started crashing, and the tech boom started eroding, and our company was really left exposed at its rawest form, which was it really was a farce. We really were only good at raising money and spending money. What we were doing is what I call chasing, and what I was doing was called chasing, which was thinking that the more we had was the token to success in life, the token to having a good life, being successful in your career, having a successful organization. But that whole model is based off of resources constantly flowing in, and it seemed like the good times would never end, but they always do, and we didn’t learn how to adapt and how to actually have a sustainable business, or for me to do things that I was actually finding meaningful.

SS: And I had this real inflection point as I was seeing not only my millions of dollars of stock option on paper turn into virtually nothing, but of course, this was also around the time that September 11th happened, and I had a really good colleague who turned out to be one of the heroes of Flight 93, Jeremy Glick, who was working for our company, and he died on Flight 93. And we really had this crisis of consciousness where we started asking ourselves what are we really doing here? We’re spending all of this money, we’re accomplishing very little, we’re not delighting customers, we’re certainly not delighting our investors anymore. What are we really doing here? And it was at that moment that I realized that I needed to go back to graduate school and just figure out what the hell was I doing the last few years, and why. And that was the start of my research as the basis of Stretch.

BB: Oh God, the story is so compelling. And I’ve got to tell you, you use the word “eerie”. It felt eerie when you were telling it because we’re seeing some of that more and more again, today.

SS: Yeah, we see a lot of chasing out there, and there’s some telltale signs in how people are thinking about their consumption. Obviously, the economy is distressed right now, but it seems to be bifurcated right now, where we’ve got a lot of haves and a lot of have-nots. And the haves, I think chasing is still very much alive, it might look in different forms, but I think just that the blind consumerism is really tainting people in terms of what their most important priorities are when there’s so much destruction and despair just around the corner. And so, I’m hoping that the pandemic really gives us an opportunity to rethink what our priorities and what our goals are, and to realize that life is so precious

SS: and to ask are we really spending our time in the way that we want to be spending our time, or are we giving into these chasing mentalities where we’re focused on comparing ourselves to others and thinking we just need to one up each other? And if we can’t do it in person because of the pandemic, it’s on Instagram, and boasting about what the latest thing we’ve done on Instagram. But are we really spending time and looking inward? Now we have the time to look inward and to think, “What is it that would make the type of meaningful and joyful life that I want? And am I spending my time that way?” And I think if most people, or I’d say a lot of people, if they had that honest reflection, and they held up a mirror, and they looked at themselves, I’m not sure they would say that they are doing that.

BB: Tell me about… Before we get into the book, and I want you to define the term stretching and chasing, because it’s central to the book. Tell me about how graduate school, post the dot com bubble, led you to becoming this esteemed endowed professor at Rice University? So, tell me where did you go to graduate school when you decided to do some reflection and study?

SS: So, I was at the University of Michigan. I was in an organizational psychology program, and my background was actually in philosophy, so I was the one person in the entire program who had never taken a psych class before. So I definitely felt like an outsider, and that had a lot of influence too on Stretch, because doing things differently is a big part of stretching. So I was kind of the person left out, who had never even taken a Psych 101 class, but I had a different way of thinking from my philosophy studies, and was really starting to just answer and try and ask questions that I’d been wrestling with as the dot com industry was beginning to crater, which is “Why, on one hand, can people be so successful and so satisfied with so little, yet, the experience I just went through, people had so much abundance, yet they were miserable and their organizations weren’t doing much better?” And it seemed like a big paradox about the amount of resources. It didn’t really seem to be the most important criterion in terms of what was driving either success or happiness, but that didn’t make any sense because, of course, the more you have, the more you should be able to do, and that means you’re going to feel better and be able to accomplish your goals, but it turned out that wasn’t the case.

BB: Define stretching and chasing for me, which is at the heart of the book.

SS: Yeah. So, stretching is really about being resourceful. It’s about doing more with what you already have. It’s focusing on not what other people have, not what you think you should need, not what you hope to have tomorrow, but what you have right now in front of you, and how can you be more creative, more productive with what you already have. And that’s hard to do sometimes because of chasing, because chasing is this cultural belief that the more we have, the more we can do. We want to solve problems, we just need more time, or we need more money, or we need more experience. And what that really does for us, it just makes us wait. How many times have you said to yourself, “If I have more time, or if I have more money, or if I just had more experience or more talent, this is what I can do.” But that’s just a delay towards the goals that we really care about. It’s almost like an excuse to do the hard work of what we actually need to do.

BB: It’s funny because I have this question for you. Let me tell the story then I’ll ask the question. So, when we read this, we were really blown away and we did exactly what you said not to do in the book, which was what, you know, run around our company, saying, “Oh, he’s a stretcher. He’s a stretcher. She’s a chaser. He’s a stretcher. They’re a stretcher. And I realized very quickly, one, the compulsion to take new information that seems really helpful and immediately turn it into binaries and diagnostic tools and labels, which didn’t work, because one of the things I realized in myself after reading this is that at my… When I’m at my best, and by best, I mean most confident and grounded, I am, I think I’m a stretcher par excellence. When I am uncertain, vulnerable, and afraid, I am… You will not meet a bigger chaser than me. I am like… When I sit down to write a book, if I feel like the data makes sense to me and I’m ready to explain what I’m learning, I just go, and it doesn’t matter what’s going on in the world, I just sit down. If I feel insecure or doubtful, I have to buy a new desk, I have to repaint my study, I have to get all new office supplies. Do we all have chaser and stretching inside of us?

SS: Yeah, I think we do. They’re not pure types. And in fact, maybe we should talk about being stretchy or being chasey because there are times when… Everyone does both, right? And I’m certainly not immune to that either; but being aware of the vocabulary allows us to hold ourselves accountable and to say, “Hey, wait a minute, I’m being chasey here. Is this really what I intend to do?” And I do think that pathologizing people and sticking labels on them isn’t helpful either because we’re all in this to improve ourselves, and once we label ourselves, it becomes hard to have that reflection, that self-reflection to be able to grow and to do better. So, we’re all going to have lapses and we’re going to be chasey at times, but the other side is we all have the potential and the capability to be stretchy. And in fact, we’re born, naturally, to be stretchy, and I think the studies on childhood and resourcefulness really show that. It’s our institutions, it’s our schools, our work institutions and our culture that really begin to stamp out the stretchiness in us by teaching us that there is the way to do things, to teach us there are ways of using resources in certain ways and to kind of think within the box and not out of the box.

SS: So, I think our goal is to try and navigate these institutions and hopefully eventually change them in ways that promote stretching behavior and don’t spoil the natural gift that we’re at. And there’s a really easy way, if you’ve got young children around then you can do what I call the frying pan test, which is give a young child a frying pan and it’s a musical instrument, it’s a step stool, it’s a bathtub for action figures or dolls, on a bad day, especially in the midst of a pandemic, maybe it’s a weapon to knock a sibling if they’re really frustrated. You give it to us, and we can cook in it and make a scramble or something in it, and that’s the best we can do because we’ve been acculturated to use things in particular ways. And what that does for us is it takes away the untapped potential of all of the things around us, and we miss out on that.

BB: God, that’s so good. I could just stop here and be like, I’ve learned the frying pan. Okay, I want to read this quote from Jim Collins. Jim Collins, for those of you unfamiliar with his work, is the author of From Good to Great, and Great by Choice. And I think it’s fair to say that… Would you agree that Good to Great is a business classic, Scott?

SS: Yeah. There are very few books… If you said classic, he would definitely be in the top 10 all-time list, I would say, if not top five.

BB: Yes, if not the top five. So, this is what he wrote about Stretch: “I always appreciate a book that challenges me, forces me to think and creates constructive discomfort. And I especially value such a book when its key conclusions have a base of research. Dr. Sonenshein has accomplished all this with Stretch, and I am thankful for the chance to grow from reading his work.” So not only yay for you. That’s the top… So that’s the top endorsement on the back of the book. But this term “constructive discomfort”, I… Let me tell you the most, the hardest personal thing for me, reading this book, was I’ve had a fair amount of success in my career, and I would attribute a lot of that success to my scrappiness and my stretchiness. I sold books out of the back of my car. I was just… All I needed at that point was like the money-changer belt. When I had t-shirts that… We mailed them from my house… We did, I self-published my first book because no one was interested in a book on shame, and I had to borrow the money from my parents because I was in graduate school, Steve was in medical school, and we were broke.

BB: I get stretchiness. I understand the power of stretchiness, but as success has come, I find myself being less and less stretchy. I find myself becoming more chasey, in some ways, more fearful. And there’s something that I want to pause on, and I’m not going to be able to articulate this in a way, so maybe you can unlock it for us. My success, in some weird way, has taught me how to chase. Before my success, my intuition was to stretch. Is that possible?

SS: Yeah, it’s not only possible, it’s very common because what happens is people are resourceful by circumstances, so you’re finding yourself without a lot of resources, without a publisher trying to get your book and your ideas out there, and you’ve got to be scrappy because you have no other way of doing it. So, in that case, being stretchy is pretty natural. The more challenging circumstance is how we can be stretchy when it’s a choice, and what we need to realize is that stretching is not something just when our backs are against the wall, though certainly, that’s really helpful and you were able to get your book off to such great success under such constrained circumstances, but being stretchy is something that’s also helpful when we’re already successful because it allows us to continue to create and innovate, getting the most out of what we already have. It’s not about just doing more with less; it’s about doing more with what we already have. There’s folks in the book that I profile that are millionaires and billionaires and have stuck with this lifestyle because they realize that this is a mindset that has brought them success, and it’s going to continue to bring them success because they’re going to focus on what it is they’re trying to accomplish.

SS: Once we get chasey, we start thinking about what we have to do because it’s expected of conventions. We’re worrying about what other people would be doing in these circumstances, and we’re getting away from our own goals. And you see this a lot with organizations. They start up as the scrappy, resourceful business, and then they move into the nicer office building, and it begins to change the culture of the company because, well, look, now we’re no longer the garage start-up, and we’ve got all these nice things, so maybe I’m going to not have that sense of urgency, not think as creatively as before, because I’m surrounded by this… By this abundance. And that’s why, as we achieve success, we need to be more mindful of how we’re being stretchy versus… Versus being chasey, and there are some simple exercises simply reflecting about a time when we had to stretch, when we had a lot of constraints, so when you’re working on a project, thinking about that first book and what it was like, is enough to trigger that mindset to keep you being stretchy. The research finds that just writing a paragraph can get you back into that mindset. So just thinking about, do you remember that time when no one knew who I was and I couldn’t even get my book in a bookstore? It was… The car was the bookstore, how was I feeling and what was I doing?

SS: And just writing about that is enough to put you in that mindset to carry that over, to continue that stretchiness even when you find yourself in very different circumstances today.

BB: Okay. So, one of the things I love about your work is – you may not have taken a psychology class when you arrived at Michigan, but man, you have turned into one hell of a social scientist.

SS: It’s interesting because if you think about my career, it’s been very non-conventional, and I have a chapter in Stretch about outsiders and the power of how outsiders solve problems. So, when we’re facing some of our biggest problems, like grand challenges, like what we’re facing during the pandemic today, people who approach problems from very different perspectives, diverse perspectives, have so much to offer because all the so-called experts have been using their tools in one certain way, and they’re missing the new way of doing things. And that’s where the outsider really comes along. One of my favorite stories in the book is from a guy by the name of Gavin Potter, who’s in the UK, and he was in this competition with Netflix to try and improve their algorithm when they were trying to get people to watch more movies. And he was going up against all of these teams, teams of mathematicians and computer scientists at MIT and Stanford and Oxford, and all these places. And he was literally working in his flat in London with a computer he had to turn off at night because the fan was waking up his wife [laughter] His teenage daughter was… Yeah, seriously, his teenage daughter was his math consultant to help him with the calculus.

SS: And all these teams are trying to figure out how to solve this as a math problem, and he realized it’s actually a social science problem because so much of the ratings are based off of what you watched before, because you become anchored and biased by how you rated a previous movie. So, while everyone’s trying to solve the hard math problem, what really helped unlock this Netflix prize that awarded over a million dollars to helping improve the algorithm was really just about understanding human nature, that says if we just watch the movie that we like, it’s going to impact the next movie that we rate, and no one else was able to figure that out, because they were busy doing fancy math and he was doing something very different.

BB: Yeah. It’s the outsider perspective. So, I want to see… There’s a part in the book, is that part of the 166 grand challenges study? Can you tell us a little bit more about that study?

SS: Yeah. So, this is a study looking at these grand challenges, think about eradicating a disease like what we’re facing right now, how to get vaccines fast, to cleaning up the Exxon Valdez oil spill. These are our biggest challenges we’re facing. And in this study that looked at 166 of these grand challenges, it was across 10 or 12 different countries, different research and development labs and companies, and there’s a really simple question the researchers were asking. They were asking, “To what extent does a scientist’s background in an area of the challenge impact how well they can solve that challenge?” So, in other words, how well can the biologists solve the biology problem, and you probably would say to me like, “Well, Scott, why would they even study that? It seems…

BB: Yeah.

SS: obvious.” The biologist, of course, is going to get all the biology grand challenges, and so on. And what’s so telling is not only did the study not show that positive correlation, it actually showed a negative correlation. So, the biologists actually solved the chemistry problems better than the chemists, and the chemists solved the biology problems better than the biologists. It was the exact opposite of what we think, which is just completely remarkable because we think expertise is really what matters, and that someone who doesn’t come to the table with the most knowledge out there has very little to offer. But, in fact, these are the hidden gems that help us solve our problems that we need to be empowering more.

BB: To me, this is… People ask a lot… People ask me pretty often, to be honest with you, how is it that you make connections between things that are seemingly unconnectable, especially around behavior, emotion and thought? And for many years, I thought, well, it’s because I’m a grounded theory researcher, and I study people, and that’s my expertise, but really, after reading Stretch, what I realized was I’ve been an outsider my whole life, and my social wellbeing and my emotional wellbeing was completely dependent on being able to understand people, and how what they experienced and were feeling drove how they showed up and behaved.

SS: Yeah. Yeah, and I’m totally with you, because that’s what I feel. And it’s sometimes a hard space to occupy, of course, because you never feel like you fit in a specific box, and it’s… I remember even going on the job market the first time as a faculty member, and people are always, “Well, what box are you in?” And I’m like, “Well, I span multiple, multiple boxes. I don’t want to put myself in a box.” And it’s… When we’re stretchy, we’re becoming comfortable with realizing that it’s okay not to fit into that single box, and we can be almost like multilingual, and it’s about making connections between different parts of problems that we’re solving. That’s a really powerful superpower to have because it allows us to look at things in ways that other people have overlooked.

BB: I want to ask you a question that, again, I don’t know if I can frame it up well so you may even have to help me ask the question. See if you can follow me. When I think about what’s happening right now around the racial reckoning and this fight for racial justice that is long overdue, that I’m super-committed to, I know you’re committed to it, because I know you outside of this. When I look at the issues that we’re facing with police brutality, anti-Semitism, and nationalism, I often wonder if the moral imagination that it’s going to take to fix it and to create more justice, environmental justice, social justice in the world is going to come from stretchy outsiders?

SS: I think so, because what we’ve seen is the status quo is clearly not working, and the so-called experts have not figured out a way, and we’re seeing, in really dramatic and unfortunate ways, just a lot of our social institutions beginning to crumble under all of this anxiety and stress and despair and unfairness of what’s happening out there. And it’s almost like we’re slogging away, just trying to get by, and not really touching the root of the problem, almost because people might be afraid to touch it, and it’s not just going to disappear by itself. And we do need solutions that help bring people back together and start to treat everyone with the worth and dignity that they deserve. And this reminds me of a study by Gordon Allport from the 1960s, and what he was studying during that was, again, groups that were just not getting along, and trying to put them in the same room. And he realized it doesn’t actually take a strong intervention to bring people together. It’s simply just about spending time together. And right now, what we’re struggling with are just these narratives, where we’ve got at least two very different camps, and telling stories in their heads that are just completely annihilating each other. And we need to bring those stories together and help realize that we have so much more in common that bonds us together as humans than we do apart. And that our country has a really sad history of how it’s treated certain groups of people.

SS: And I think we need to really get out there and help bring more voice to Black Americans and other underrepresented minorities, and just stop ignoring that and thinking this problem is going to go away. So, having outsiders come in there and think about ways of bringing groups together in ways that haven’t happened before, I think, is really helpful. But something needs to start soon because these stories become self-perpetuating over time. And unless we find a way of re-narrating those stories sooner, they’re just going to become further and further ingrained, and it’s going to be that much more difficult to dig out from under them.

BB: Is there a relationship… When we talk about problem-solving, whether it’s, again, the Exxon Valdez or issues of racial injustice or the pandemic, is there research around the relationship between creativity and imagination and stretchiness, or do the most creative and great ideas come from folks who chase and set up the biggest labs and the… What do we know? What do you know?

SS: Yeah. So, the creativity is a function of the stretchy mindset, and so that can come from just naturally being resource-constrained, like when you were trying to launch your first book, or it can come from just getting into the stretching mindset, through just thinking about a time when you were constrained. And what the science teaches us is that when we face… When we face constraints, we have almost permission, we give ourselves this kind of funny permission to use our resources in different ways. So, when we have abundance around us, we can only see a chair as a chair because we have kind of the archetype type of, well, a chair is something that we sit in. But what’s interesting is that when the mind is in this more scarcity, this stretchy-type mindset, we begin to see the chair as different things, whether it be a stool or a back scratcher, or whatever else we might come up with it. So, we can unlock creativity, and we tend to think that creativity is something that people are born with. And I’m not an artist, so I’m not really creative.

SS: But there’s another type of creativity, it’s called little-c creativity, and this is the engine that allows us to solve problems, whether it be around the pandemic, or racial justice, or day-to-day problems in our work life. It’s this little-c creativity that we get this license, this permission slip to unlock once we embrace this stretchy mindset. So, the research currently shows constraints make us more creative, and I think that’s why they have the cliché that necessity is the mother of invention.

BB: Tell me what word you’re using in front of creativity. What kind of creativity is this?

SS: Little-c creativity, so just the lowercase c as a…

BB: Oh, little-c.

SS: Yeah, as opposed to just thinking big creativity, like I’m going to go compose a work of music or make beautiful art. This is the… Little-c creativity is the type of creativity that allows us to solve problems, and that is a function of our stretchy mindset.

BB: Okay, I need you to have my back on something really big. Are you ready? I don’t want you to ever lie about the data, but I need you to have my back on this.

SS: Alright, I’ll see what I can do. Bring it on.

BB: This drives people crazy, and it’s probably kind of a shitty thing for my family and my colleagues, but why do I write so much better under massive time constraint, so much so that I think I create it in order to write?

SS: Okay. So, I’m glad I’m not the only one who does this, so thank you [laughter] Thank you for validating me. I know that wasn’t your intention. It was supposed to go the other way around. But I’m the same way. It’s deadlines create urgency and they activate in us making connections between things that we have a hard time seeing. When we have abundance, we have what scientists call slack resources. So it could be like, well, I don’t need to finish this paragraph or make this connection because I have another three weeks until this deadline is up. And so, what happens is we just squander those three weeks until it’s midnight before it’s due, and then miraculously the idea comes to us. So that’s the first thing going on. But the second thing I should point out is so much of our thought process is subconscious, so when we’re not working, we’re going for a walk… I love to walk, I know you love to walk too, we are constantly thinking about our problems even if they’re not top of mind, and so we’re beginning to develop ideas in our minds that when that deadline hits, we’re not starting from scratch. The mind has already been working on some things even without us realizing it, and we’re just activating it during that deadline.

BB: Can I tell you a funny story? So, I’m getting ready to start my sixth or seventh book. And when the kids were little and I was writing my first book, Steve was like, “Okay, I understand you have to write this weekend. I’m going to take the kids to San Antonio and go visit my mom.” And I said, “Great.” And so, when he came home, he said, “Did you get a lot written? Was it productive?” And I said… I was going to lie, but then we have this rule where we don’t lie, so I was like, “Well… ” He goes, “Did you write… Did you not write a lot?” I said, “Well… ” He goes, “Did you write anything?” And I said, “No, I didn’t write a word.” And he was gone for a three-day weekend, and he said, “Well, what did you do?” And I said, “I watched like 46 episodes of Law & Order.” And we had a fight, like we had a fight, not like a fist fight, obviously, but we had a really uncomfortable argument, and probably that was… He was home on a Monday afternoon, because it was a three-day weekend, and then, on Thursday, I said, “Hey, I’ve got my first draft ready.”

BB: And he’s like, “When did you write that?” And I said, “Oh, between breaks at work, and on lunch.” And now he still can take the kids away when I’m writing, and he’s like, “Okay, we’ve got to go. Your mom’s going to watch Law and Order, and she’s going to do a lot of walking, and she’s going to reorganize stuff and clean up.” But I need to do something that rests my brain, and Law and Order is so formulaic and easy, because I think what you’re saying is true. All my creative stuff bubbles up underneath that, or something. Is that weird? True?

BB: No, it’s not weird at all because, again, so much of this mindset is trying to free ourselves from what’s happening out in the world, and when we are walking or watching Law and Order and doing something that doesn’t require a lot of thought, our mind actually becomes looser because it’s not focused on the task right in front of us. So doodling, or something, in school, I know teachers would give students a lot of problems with that, but that actually – people are still processing information, and it allows them to be more creative in their problem-solving when they’re doing something. So the trick here is to do something that requires a low amount of thought, and then that’s when the brain starts thinking about these things in the background. So doing doodling, walking, watching TV could work. And that tends to be more creative than if you were doing nothing. If you just try and think about the problem, you begin to tighten up how you think about your resources, whether it be ideas or knowledge structures, so you’re not as creative. So, it’s doing a low amount of things that takes your mind off the problem actually allows your brain to work on the problem without the stress or the pressure. So, you go back to that Law and Order, and you can tell Steve that you are busy working while you’re watching TV.

[laughter]

BB: And let me tell you, I didn’t know about the term doodling, but I must be wired for that hardcore, because the other thing is, when I get stuck in writing, I play ping-pong for hours.

SS: Yeah. Yeah. No, that’s another good one. The key… The one caveat here is not to be doing two things that require a lot of thinking at the same time, so like multitasking is absolutely terrible for this, but ping-pong, when you’ve got a big problem you’re thinking about, that’s awesome.

BB: Okay. So help us draw the line. So, we’re not… Well, because I’m not thinking about my ping-pong game when I’m playing ping-pong, I’m thinking about other things and just kind of… I’m just going through the motions of ping-pong. So, there’s a difference between doodling and multitasking?

SS: Right. When you’re multitasking, which science shows on that, we don’t actually multitask. What we do is we switch between different tasks just very, very rapidly, and we don’t see that, so it seems like we’re multitasking, but if you’re trying to write a book at the same time and you’re typing while you’re trying to do a math problem in your head, you know, that’s never going to work. And that’s because the brain just doesn’t work that way. So doing something that requires very little thought process: ping-pong, walking, watching mindless TV, that allows the brain to reserve its power for the problem that you’re trying to solve without needing a lot of computational power to do this other activity. But once those two activities become things that require a lot of concentration and effort, all bets are off, and multitaskers, actually, the science says, are about 40% less productive. So you don’t want to go down that route.

[music]

BB: That’s bad news for me, y’all.

BB: Okay, I want to get into a topic that is bad all the time, it seems really weird right now during the pandemic, which is comparison. I have 55 planned activities for my kids, I’ve developed a six-pack from my new exercise regime, and I’m making sour dough bread, and I’ve redesigned my house. Tell me about the Olympic medal study and your takeaway in terms of stretching and chasing, around that study. This study freaks me out like big-time.

SS: So, this is a study comparing medalists at the Olympics, and what the research was looking at was how are people happy and what are they feeling after the Olympics? And you would think that there would be a very natural hierarchy to this, obviously, you win the gold medal, you’re going to be the happiest, and then the silver medalist, because they came in second, and second is awesome still, and then the bronze medalist. And then, after that, the people who didn’t medal might actually be a little upset because they didn’t even get a medal. But actually, what the research shows is the least-satisfied people among the gold, the silver, the bronze, and even the non-medalists are the silver medalists, which is crazy because…

BB: Oh my God, it’s crazy.

SS: They came in second in this… In Olympic competition, and the question is “Why?” And it really goes to comparisons and what your reference group is. The silver medalists aren’t appreciating and grateful for coming in second place in this world-class competition. They’re thinking about how they just missed the gold medal, and how close they were to that gold medal, and that changes their perspective inordinately, and they’re less happy. And you can look at footage of Olympic medalists and you see that the silver medalist tends to be the least happy of the group.

SS: The bronze medalist, who objectively performed worse than the silver medalist, is much happier than the silver medalist because their perspective is also very different, they’re just grateful they got a medal. And I think that teaches us an important level, especially in the pandemic, about who our comparison groups are, because social comparisons are largely human nature, because it’s a form of making meaning, it’s a way of taking stock of how we’re doing. And it’s sometimes hard to do that without looking across the world. And I think, in the pandemic of your social media, these problems… Our reference groups are expanded because we’re not only just looking at our neighbors, which also is problematic, in some respects, and we can talk about that, but we’re looking across, largely, the world right now and seeing all of these things being done. And it’s like, my goodness, I’m like trying to get my work done and now you want me to run this school and we’ve got eight subjects with my kids, and by the way, we’re going to pick up three different hobbies during the time and start the remodeling job.

SS: It’s overwhelming, just thinking about it. And I think we need to start dropping those comparisons because they’re unhealthy for ourselves and they don’t reflect the goals that we want. With stretchy, when we’re being stretchy, we’re thinking inward about our own goals, not what our neighbors are doing, not what our neighbors’ kids are doing. And if I can just lead you towards just a second to this study in the book about grass, which I think is…

BB: Oh God [laughter]

SS: Emblematic of the blueprint because there’s the cliché that says the grass is always greener, and this idea that people spend a lot of money and a lot of time trying to get their grass pristine looking because they want to outdo their neighbors. The lusher the grass that you have, the more successful you are, the better life that you live is kind of all wedded in our ideas of the American dream and home ownership. But what’s so interesting about the physics of how grass works is when you are literally peering over your fence, looking at your neighbor’s grass, their grass, because of the angle you’re looking at it, looks greener, even if it is actually the same lushness as your own grass.

SS: And that’s just crazy, and it really teaches us perspective, because when we’re looking over at other people, sometimes their lives look remarkably amazing, and we know people disproportionately share only good news on social media. People talk about their promotions on LinkedIn, they don’t talk about when they got fired, and so on. So, we have a very jaded view of what other people are doing and how they’re living. And if we start comparing ourselves to them, we’re just making comparisons that we’re just destined to fail. So, we need to stop these social comparisons and realize, look, no matter… Even if their grass looks greener, our grass is really probably just as green, if not more.

BB: You’re speaking right to me. Yeah, and it’s so funny that the grass is actually greener from the other side. I mean, is that perfect or what?

SS: Yeah. No, I know.

BB: Okay, I want to talk about our kids. I want to talk about parenting. This book really woke me up in some ways. It’s also helped me learn how to talk… Both of my kids have some weird math ability where they can answer a very complex problem, like the problem of the day or the problem of the week on the board, but they don’t get good grades because they don’t show their work in the way that they’ve been taught. Like they get to the answer… In fact, there’s been a cheating accusation one way, like there’s no way you could have gotten this answer without these exact steps. And then, really, we had to walk the teacher through the steps and say, “This is how it came to be.” How has this research changed how you parent your daughters differently? What have we learned about coming at problems differently, about resources? Help us.

SS: Yeah, I think parenting is always, always challenging, and I certainly started rethinking about my own. I’ve got 13 and 8-year-old daughters about… Thinking about what it would be like to raise stretchers because there’s things we can control in life, and things we can’t control in life. And sometimes, just the ups and downs of life, we can’t control the amount of resources we have. So, for me, it’s really important to instill resourcefulness. So I know, as a parent, my first instinct is you want to be good to your kids, and you feel like they ask for something, you want to give it to them right away. They want a new toy, you want to go out and buy it for them, especially if you can afford it.

SS: And what I’ve been trying to do is really instill in them that, look, you’ve got lots of stuff already around you. How might you put these things to different use? So, you can combine different types of toys together and then you’ve created an entire new experience. So that was kind of like the younger phase of teaching them to get creative with it. And what they’ve realized is there’s actually a lot of pleasure you get into being creative and using things in different ways. And so I think they got that lesson. So that one was a little easier, maybe younger kids are easier, but as my kids have gotten older, I think we’ve come across the education system that you’ve seen with your kids, an education system which teaches conformity, which teaches people and children to think in very specific ways.

SS: And what I’m trying to encourage them to do is to recognize that sometimes, look, you’ve got to learn to play by the rules of the game, and that’s just the pragmatic thing, so I’m not going to tell you to tell your kids, or I’m not going to tell my kids, that says, just blow it off when the teacher wants things. There are just people who are going to demand that certain things go in a box, and that’s a useful skill to have, but I don’t want that to take away from the gift that you have and the gift that I think every child has, which is you’re a unique stamp on the world, the way that you approach problems, the way that you look at problems. So, I’m trying to empower them to think about… Even though you might have different experience, or you might not take as many classes in this area as someone else, you still have something to give. And it’s that kind of outsider perspective that can help make a contribution. Don’t just check out because you feel like someone around you has more. That’s actually the time to check in because it allows you to give a different type of gift.

BB: It’s really interesting. When I think about teaching stretching and chasing, I think about the impact of also trying to model that with our kids, right? Like also trying to… I just we’re re-releasing The Gifts of Imperfection. It’s the 10th anniversary this year. And I, as part of the 10th anniversary, I read the book because the first audio of the book was not read by me, and so our community was like, “Please read the book.” So, I read the book, and when I was reading it, I was reminded of… This was… Again, I wrote it 10 years ago, where Steve and I put a joy list together, and we wrote down all the things that brought us joy, and we actually started the exercise to make sure our acquire and acquisition list was still right, all the things we wanted to buy, all the things we wanted to earn and get. And so, we wrote down this joy list, and it was so painful because everything that brings us joy as a family, still today, has nothing to do with acquisitions and accomplishments and acquire… It was like we cook together at least four times a week, we have family dinners, we go hiking, we swim together, we…

BB: All these things that really bring us joy. And, of course, let’s get Maslow here, we’ve got, financially, all of our basic needs met. So, this is not saying, “Who needs money? Cook together.” I’m saying like, we have the basic needs met. But when I compare the joy list with our dream list about buying this or acquiring this, it was so telling about time as the resource that is just the most precious and un-renewable, right? Is that a part of stretching and chasing?

SS: Yeah, no, it is, because time is really one of the hardest resources to renew, it’s fixed. And we know, from the research, that how we spend our time and experiences we have matter so much more for life satisfaction than buying the latest fashion item or electronic gadget. So how we choose to spend our time is going to make all the world of difference. Now, when we’re stretching, we need to be more mindful of how to get the most out of our time, and this is where, when I think about everything from when my kids were really young to what they are now, is we try and create these collective experiences that allow us to do multiple things at once to save time. So, for example, I love to walk, so I would spend time walking my daughters in strollers when they were young, and that was a way of spending time with them and chatting with them while still being able to walk. Cooking is something we’ve been doing a lot together as a family as well, so we’re checking off multiple things at once and having that quality time, and that’s a way of expanding what we have.

SS: But another big part of it is just not wasting time. We waste a lot of time chasing after the things that we think we should want and losing touch with the things that really bring us meaning and joy. And I think, for a lot of people, no matter their circumstances, if they just cut out those activities and things that they’re doing that really aren’t bringing them any type of meaning or pleasure, like real, if they held up a mirror and said, “Am I really doing this because I enjoy it or am I doing this because I think I should be doing it?” I think people would find that they have a lot more time than they realize.

BB: It reminds me a little bit of my own research around comfort… True comfort versus numbing. If you want to sit down and take true comfort in watching two hours or three hours of Law & Order, go for it. But if you’re just numbing and it’s not filling you back up at all, just scrolling through or just… It’s really thoughtful. I have to say that I’m going to continue to work on the chasey in me. Oh my God, if I won the silver medal, I’d be pissed off. That is not a good part of my personality. I’d be like, “Oh no, mm-mm.” I would be really mad. If I won the bronze, I would be thrilled. I’m just happy to be here, and medal, and like wow. But that’s not a good part of me, Scott.

SS: Look, it’s hard. It’s not easy for you, it’s not easy for me, it’s not easy for anyone, but again, just calling ourselves out on it and holding us accountable for it is such an important step.

BB: Okay, you ready for our rapid-fire questions?

SS: Okay.

BB: Alright. Fill in the blank. Vulnerability is…

SS: Hard, but definitely doable.

BB: You’re called to be really brave, but the fear is real; you can feel it in the back of your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

SS: Just jump in and start acting.

BB: What is something that people often get wrong about you?

SS: That I’m always super-serious. I actually have a pretty playful side to me.

BB: I can vouch for that, actually.

[laughter]

SS: Thank you.

BB: They just can’t see your Vitae first. If they see your CV first, you’re going to have to be really… You going to have to come up with some knock knock jokes, or something. Okay, the last TV show that you binged and loved?

SS: Suits.

BB: One of your favorite movies.

SS: Back to the Future.

BB: Oh my God, of course.

SS: I finally introduced my kids to it a few months ago too, and they loved it.

BB: I got to say some of the movies that we loved, growing up, did not age well, so that one is one we’ve watched with our kids too, it’s a good one. Okay. A concert that you’ll never forget.

SS: Counting Crows.

BB: Mm, good one. Favorite meal?

SS: Anything involving dessert, I would say.

BB: Favorite dessert?

SS: Ugh. I’m going to go with chocolate babka.

BB: Chocolate baka?

SS: Babka. Yes, it’s a…

BB: Babka.

SS: Yeah. It’s like kind of a chocolate-infused coffee cake with lots of layers of chocolate, almost like a combination between a croissant and a coffee cake filled with chocolate. We’re going to have to get you one of those if you’ve never had one.

BB: Oh my God, you know where they used to sell those, that… Scott and I live close to each other. They used to sell those at Three Brothers Bakery, which is not here anymore, but, yes. Oh my God, that’s very… So, you’re a chocolate-lover. That’s chocolate-y.

SS: Yes, I do love chocolate.

BB: Okay. What’s on your nightstand?

SS: Well, right now, we’re in the middle of moving, so I’ve got a flipped cardboard box as a nightstand until our new one comes in, but it usually is sparkling water and something my kids made me.

BB: Oh my God, but that’s very stretchy of you to use the box that way. I like it.

SS: Now, we donated our real nightstands a few weeks ago, so that’s what we got.

BB: That’s awesome. A snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life right now that gives you joy.

SS: So, right before this pandemic started, my older daughter had her bat mitzvah. We had our entire family together here in Houston and, unfortunately, I just don’t know when we’re going to get back together all in the same room. So, I’m really cherishing that moment.

BB: Tell me one thing that you’re deeply grateful for right now.

SS: My health and my family’s health.

BB: Amen, right? You just… That is… Even when I see something on an email that says, “Dear Brené, I hope you’re well,” I’m like, “Wow, that just has different meaning.”

SS: Yeah, it’s no longer just something trite and banal, like when you say it to people too, you’ve really got to… You’ve really got to mean it because it’s just what’s happening right now is pretty remarkable.

BB: Okay, we asked you for five songs that you can’t live without. So, you’ve got “Don’t Stop Me Now”, by Queen, “Walking on Sunshine” by Katrina and the Waves, “Stick It To The Man”, which is from the Broadway musical School of Rock’ written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Glenn Slater, “Only You” by the Platters. Now, is that the, [singing] “only you”, that song?

SS: Yeah, you got it.

[laughter]

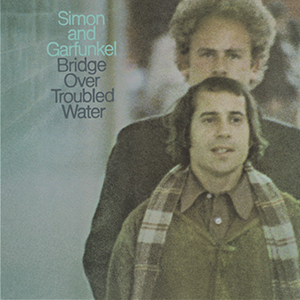

BB: Oh my God, I love that song. And then you’ve got one of my favorites on your list too, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon and Garfunkel. What does this playlist say about you?

SS: So, I think it says you got my playful side in there with “Don’t Stop Me Now”. I think “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is just… It’s such a calming song, and it’s something that, with just everything going on in the world right now, from the pandemic to racial injustice, to just uncertainty, it’s something that just brings me a lot of calm right now. “Stick It To The Man” I think is just… It’s kind of like that inner rebellious part that I have, that says I don’t want to be a conformist, even though I’m living in a system that completely rewards conforming. There are just times when we just want to get out there and revolt. It’s also an amazing workout song too, so hey, I love doing my workouts to that song. “Only You” was a first dance at… When Randi and I got married, and I think it just reflects just the specialness of our relationship, and what she’s really meant to me in our lives. And “Walking on Sunshine”, what a fun, happy, uplifting song, and if you just change the letters around, there’s “Walking on Sonenshein”, and it just gives me the most…

[laughter]

BB: Walking on Sonenshein! You got your own song. Oh man, okay.

SS: Close to my own song as I’m going to get, so I’ll take it.

BB: I’m going to start calling you Scott Walking-on-Sonenshein. Thank you for being with us on Unlocking Us and thank you for this remarkable book.

SS: Thank you so much for having me on.

BB: It’s just a total delight, and I will… We’ll walk soon, yes?

SS: Yeah, we’ll definitely walk soon, and I’m going to bring you a chocolate babka.

BB: Oh my God, then we’ll walk a lot.

[laughter]

SS: We’re going to need to.

BB: We’re going to need… Wait, just so that this Unlocking Us community just feels like motivated, how many steps do you get in a day?

SS: So it could be between 18 and 20,000. I am a serial walker. My meetings we’ll go walking. My ideation process, we’ll go walking. So, it’s a lot, but you certainly don’t need to do that many to feel good about yourself, but that’s kind of my thing I do.

BB: Yeah, it is. And we’ve had meetings before, walking meetings before, which are so… It’s just so much better. I’ve got… At the end, I’m sweaty, I got no notes, but my life has been changed, so I love it. Scott, thank you so much. I really appreciate you.

SS: Alright, thank you too. Take care.

[music]

BB: Okay, you all, isn’t Scott Walking-on-Sonenshein just the best ever? I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. I just have so much fun talking to people who are dedicating their careers to unlocking us. Do you see what I did there? Ba dum bum ssh. So, his book is called Stretch: Unlock the Power of Less and Achieve More Than You Ever Imagined. You can find it wherever you buy books. It’s wonderful, it’s a fun team read, if you’re working with a team; it’s a good family read, a great family discussion. You can follow Scott on Twitter @ScottSonenshein S-C-O-T-T, and then Sonenshein is S-O-N-E-N-S-H-E-I-N. Instagram is scott.sonenshein, and his website is www.scottsonenshein.com. He’s nothing if not predictable on these social media and websites. Speaking of books, just some fun news, in case you haven’t heard or seen, the 10th anniversary edition of The Gifts of Imperfection launched today on September 8th. Really exciting. This is the book that launched our community, and it was so weird to kind of re-do it because the… When we asked people, “What do you want?” They said, “Don’t change anything. Don’t change any stories. Don’t change the text. Give us a new foreword, let us know what’s been going on, but don’t change anything.”

BB: So, I wrote a new foreword, we didn’t change anything, but we are going to do a webinar series on it. We have a new hub on brenebrown.com. You can take a free assessment called the Wholehearted Inventory, which we spent several years developing and validating, and it will let you know kind of what your strengths and opportunities for growth are, based on each of the 10 guideposts. We also have beautiful graphic design downloads that you can get for free on the hub, so visit brenebrown.com for all things The Gifts of Imperfection. Join us on the webinar series. That’s going to be really fun. Barrett? I’m looking at Barrett. Am I forgetting anything? You want to say hi to the people?

Barrett: Hi to the people.

[laughter]

BB: Y’all have a good one. Stay awkward, brave and kind.

© 2020 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.