Brené Brown: Hi everyone. I am Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. We are back with part two of our podcast with Doctors, Erika James and Lynn Perry Wooten, and we are talking about their new book, The Prepared Leader: Emerge From Any Crisis More Resilient Than Before. I loved the first part of this conversation, did you?

Barrett Guillen: I loved it.

BB: And now we’re going to get into some nitty gritty. [chuckle]

BG: Yeah.

BB: It’s not easy, this whole idea that being a prepared leader is almost impossible if you’re a protecting ego leader.

BG: Yeah.

BB: Yeah, you can pick, prepared or protected ego, but you just really can’t have both. They’re mutually exclusive. If you listened to the first episode, which you really should listen to the first episode of this before this second one, you’ll know I love this book. You’ll know that we’re going to read it here. It’s tactical. It’s practical. It’s based on such great research. They spent decades studying crisis management, what to do and what not to do, and how it works. It’s great relatable stories, and then just things that I love, like chapter recaps at the end, and tables that show everything that they’re talking about. It’s just so good.

[music]

BB: So quick bio, if you are just joining us, we are talking with Dr. Erika James, who became the dean of the Wharton School on July 1st, 2020. She’s trained as an organizational psychologist. She is an expert on crisis leadership, workplace diversity and management strategy. Before being at Wharton, she was the dean at Emory University’s Goizueta Business School for six years. She is an educator. She is an academic. She’s a scholar. She’s a theorist. She has so much to share with us. Joining us is Dr. Lynn Perry Wooten, who is a seasoned academic, an expert on organizational development and transformation, and is the ninth president of Simmons University and the first African American to lead the institution. Before she was at Simmons, she was the dean at the Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, and before that, she served on the faculty of the University of Michigan, Ross School of Business. Interestingly, Lynn and Erika met each other in their PhD programs at Michigan and have been friends since, and co-conspirators and collaborators, and truth tellers and friends, and back-up and all the good stuff that we all need. Let’s jump in.

[music]

BB: So just a quick welcome back to Erika James, Lynn Perry Wooten. We are talking about The Prepared Leader: Emerge From Any Crisis More Resilient Than Before. The book has just come out from Wharton School Press. I’m having my leaders read it. It is the real deal in terms of… I thought about this a lot when I was reading this book. Very early, my first non-academic speaking event, so this wasn’t grand rounds, or this wasn’t at a university, this was like some people asked me to come speak. And I don’t know how this person got the recommendation, but right before I went on, she was practicing reading the bio and she said, “Oh my God, you’re a shame researcher? I thought you were a happiness researcher.” And my real response was, “I don’t know much about that, but… ” And I said, “Well, I talk about the things that really get in the way, not just what we should be doing.” I just think it’s such a fool’s errand, even when I read articles that are just like, “Here’s what you should do,” and don’t address the real humanity that gets in the way sometimes of doing it. And every time you give a strategy here in this book, you prepare us for the gremlins that are going to get in the way, for those little voices that say, “This is scary, what if I’m wrong, should I ask someone else?” So, it’s so tactical this book. Did you want it to be more of a handbook than a theoretical overview?

Lynn Perry Wooten: Our last book was the heavy theory. We wanted this time someone going from Chicago to LA to pick up the book and say, “How can I be a prepared leader?” And have all the sticky notes like you have, take notes and then go into their C suite, and have everybody else read the book and discuss it. What’s the next crisis on the horizon, and what are the tips and tools I can use from this book?

BB: I want to start with a quote that’s at the top of chapter seven, I’m on page 85 in the book, it’s a quote from Marion K. Pinsdorf, that says, “All crises are global.” Unpack that for me.

LPW: I’m American, I admit it, and I think all crises are in the United States. I’m myopic, and I had this viewpoint. But the more and more we study crisis, it’s just not isolated to one community, one geographical region. It’s all a global crisis. What happens in the United States is going to impact the other parts of the world and vice versa. And so, we want leaders to lead, after they read our book, to understand you need a global mindset, and part of having a global mindset is being able to frame the crisis, and to think about the culture context and the greater mega community you need to get back to business recovery.

Erika James: The intersections that exist. We are too deeply embedded in every facet of society to think that what happens in one region of the world isn’t somehow going to manifest and affect people in another part of the world. The pandemic is an extreme example of that for sure. One of the things that I think is important to highlight is we’ve gotten very comfortable… Prior to the pandemic, we got very comfortable with describing every inconvenience as a crisis. Even our language, we say things like, “Oh, I’ve got to spend all my day fighting fires. I’ve got to put out a crisis of the month, or a crisis of the day.” So, we just began to assume that anything that was inconvenient or troublesome was in fact a crisis, and I think the pandemic actually helped us realize what a true crisis is. So, when this phrase, this quote, “All crises are global,” we’re not talking about the day-to-day problems that you find inconvenient and that you describe as a crisis. We’re really talking about things of such significance that the likelihood of them happening has implications around the globe.

BB: Wow. As a language person, I’m really struck by something here. When I was doing the research for Atlas of the Heart, and I got into the academic literature around stress and overwhelm, and how these are two very different constructs, and how often I thought about for myself, language doesn’t just communicate emotion. It actually shapes our neurobiology, our physiology. And I thought, how many times a day, sometimes, I use the term ‘overwhelmed’, when really, I’m not overwhelmed. Life is not actually unfolding faster than my system can handle. I’m actually stressed. It’s more whack-a-mole than it is complete overwhelm. And just changing my language, so now I say to myself, “We know, from the research, there’s one antidote to overwhelm, and it is nothingness. We literally have to get up, walk around, take a break, walk the parking lot, meditate.” You’ve got to do nothing in order for your system to reset. So now I say to myself, “Brené, unless you’re prepared to get up and do nothing, unless it’s that bad, call it stressed, don’t call it overwhelmed.” We completely are hyperbolic around the term “crisis.” So, what is a better way? Should I just be saying, “Well, this feels like a serious challenge. I’ve got to deal with some problems today, or I’ve got to deal with some sticky stuff, or like what… ” Do you have a good word for us?

LPW: I use challenge a lot.

EJ: And challenge means it can be overcome, right?

LPW: Right.

EJ: So, to me, the distinction that I make when I’m working and talking with people is, a problem is something that you’ve likely experienced before, there’s a solution for it, you have the resources to address it. Resources being the human capital, the financial capital, the know-how. And if those characteristics exist, then whatever threat you’re facing is something that you can address. It’s inconvenient, you’d rather not have to devote your resources to that, but the reality is you know that you’re going to be able to overcome this. And when we refer to problems as crises, when something does happen that is significant, we’re not equipped. And we’ve never put the time and the willpower into understanding what it actually means to equip ourselves and our organizations for things that we’ve never experienced before.

LPW: And then that’s where the competencies in the book come up, Brené.

BB: Yeah, this is such a profound moment, because language is so important, not only in our personal lives but also in our work lives. In mental health, when we talk about a crisis, we think we’re outside of the normal distribution of behaviors that are predictable, knowledge we can draw on, and it’s almost the same in a business crisis. And so, I think this is really important. Let’s talk about, in a crisis, what role and what level of importance does communication play?

LPW: I say communication is everything. Communicate, communicate, communicate. In the book, when we talk about trust, we talk about communicating being one of the three Cs. If you’re going to build trust among your various stakeholders, one, you have to communicate; two, you have to demonstrate that you’re competent; and you have to think about the psychological contract that you have with your employers. My students, for example, my alum. It could be your shareholders. And we know that communication has gotten very complex since Erika, and I first started studying crisis. [laughter] You have social media, you have newspaper, you have television, you have internal communication, you have external communication. So, every phase of that crisis, you have to think about what is the message that I want to communicate? How will the receiver receive it? And am I listening and incorporating feedback? A lot of the time, in fact most of the crisis management research started in the communication field, and we wanted to expand it beyond communication to really what leadership looks like.

EJ: Communication is a necessary but insufficient aspect of leadership during a crisis.

BB: Drill down.

EJ: So, you cannot expect your organization to come through the crisis if you are not transparent and sharing information. It’s important to realize, it’s not always the CEO who’s the best most effective communicator. So, identifying who in your organization should be that person that’s doing the communicating is key. But if that’s all you do and you don’t do some of the other competencies that we describe in the book, you’re not willing to be creative, you’re not able to take risks, you’re not willing to make sense of information around you, those are other aspects of leadership during times of crisis that will allow the communication to be more effective.

LPW: I think the other thing important about communication goes to something you say in Dare to Lead. The organization and the individuals have to know their values. And those values have to be consistent in the communication, and they have to speak to them and walk the talk.

BB: People have to feel your values in what you’re saying.

LPW: Right, you have got to feel your values, or your communication, I’m not going to believe you.

BB: Let’s talk about CrossFit.

LPW: [chuckle] Yeah.

BB: Yeah, let’s talk about CrossFit as an example.

LPW: Yeah.

BB: Tell us the story.

LPW: So, this notion of CrossFit and the CEO using technology to communicate, and maybe not communicate things that were the norm during the George Floyd. So, if you look at, I think it’s page 87, because I wanted to read, I had marked it after you said. Let’s see what page it was there.

BB: It’s 87.

LPW: Yep, it’s 87.

BB: I have it marked.

[laughter]

LPW: Right, I knew you were right. You have this notion, of posting a comment on social media that made light of COVID-19 and the Floyd murder. All of us can remember what we were going through. I think that that had to be about June of 2020.

BB: Yes.

LPW: We realized we weren’t going back to work two weeks now. We were stuck in our houses. And Erika and I definitely remember, we had George Floyd, and our two kids were graduating from high school. So, it was a June, I remember. They weren’t getting their normal high school graduation. And so we had this notion about this racism as a public health issue, and he tweeted, “It’s Floyd-19 this,” and a slew of remarks leaking to the press about Floyd’s death that had a public backlash. He was insensitive to what’s going on. He was not using the right platform. And what happened is, in less than a month, they lost thousands of their affiliated gyms, and people who believe in this CrossFit program. More importantly we talk about in this book as just as important is he failed to understand the global dimension. The George Floyd incident and Black Lives Matter, it wasn’t only here in the United States. You could turn on your TV and you saw the entire world feeling the pain of what was going on here in America. And so, this is someone where we needed a more emotional intelligence, we needed the sensitivity, we needed the respect for diversity of what was happening in the world.

BB: I have friends today all over the world that said George Floyd’s murder changed the way they work, changed the way they think, changed their offices, changed their businesses. Long overdue and still ongoing racial reckoning.

LPW: It’s the biggest change I’ve seen in my life, because I’m too young to remember King, but I had not seen anything relating to race relations that we’ve seen in the last two years since George Floyd.

EJ: Right. And in the CrossFit example, he was literally tone deaf to what was happening, and insensitive to the cares of his consumer base and his gym owners and just didn’t see what the rest of the world saw or didn’t care.

BB: Great consequence. There’s something I say, and I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I say it a lot when I’m working with companies, and I’m open to hearing that it’s off or not nuanced enough. I want to learn. It seems to me that if you wait to try to build trust as a leader until you’re in a crisis, you’re too late.

EJ: So, this is my hot button issue.

BB: Oh, I love it. I got her hot button issue. [laughter]

LPW: I could see her getting hot, Brené.

BB: I did see Erika leaning in a little bit. Yeah.

EJ: I read something, and I completely agree, when you talk about soft skills, and we always put soft skills, in air quotes. What I say is that the soft skills are the hardest things that we ever do. And we’ve got to start treating them accordingly, which means practice.

BB: Skills building. Yes, right!

EJ: Skill building, in this instance. And so, part of those soft skills are building really high quality, effective relationships, relationships that are based on mutual trust. And if you wait until you need something from your people or from your team or from your customers, if you haven’t done the pre-work to build that set of trusting relationships with those stakeholders, what on earth makes you think they’re going to be there for you in your time of need? But if you’ve done that work in advance, most times people will walk through fire to help you.

BB: God, it’s true, right?

LPW: Or give you grace. And so, Erika likes to call this the trust bank.

EJ: Yeah.

BB: We call trust the marble jar. It’s like, it’s a collection of small moments collected over time and moments from acknowledging that you’re being overlooked in a meeting and saying, “Let’s work on this together. I’m not going to swoop in and rescue you, but let’s come up with a strategy so you can be heard,” to, “How’s your mom’s chemotherapy going?” To a collection of small moments that add up to something that in a crisis people will. If the jar’s full, I’ve seen people do extraordinary things for other people.

EJ: Yeah, yeah.

LPW: And it takes lots of time and energy to make the jar full.

BB: God, it takes so much time.

LPW: And especially, we were new leaders. So, we talk about, in the book, we started our job in the middle of the pandemic. Many of the people in our leadership team, we never got to meet in person until six months or a year later, and so we had to think of creative ways to build up the trust jar.

EJ: There were times when I was, being at Emory University, at the Goizueta Business School, and I had an incredible team that I was working with. And it was not uncommon for me to talk about my team and use the word, ‘love’. I loved that team.

LPW: She did. [chuckle]

EJ: And there were times when I would get emotional, not woman crying in the office, but woman either so happy about something that we’ve done together as a team. And I remember, early in my two years now at the Wharton School, first year being completely online, we didn’t really have those… I hadn’t been able to build the same quality relationships yet. And something happened and I was telling my former colleagues and they said, “Oh, did you cry?” And I said, “No.” And they said, “Oh, that’s because you don’t love them yet.” [chuckle] And I love my team now, but in those early days when it was really difficult as a new person coming into the organization to try to build relationships over Zoom, it was hard to feel that connection, that interpersonal, emotional connection to form those relationships. Now that we’ve been back in person, I, of course, can look and see so much about what I love about the people that I work with and the people that I’m doing work for, which are our students and our faculty. And I think that’s so critical because people feel that and they want to reciprocate, and they want to support you, and they want to help you through really difficult decisions.

BB: God, it’s true. We are just neurobiologically hard-wired for connection.

LPW: We are.

BB: And when we make those connections, it’s pretty incredible what we can do together.

LPW: And we need connections to be prepared leaders. And like I said, we moved to new cities and new jobs in the middle of a crisis and had to think about ways to build connections.

BB: Well, this goes back to where I wanted to start. Were y’all scared respectively going into these positions? These are hard jobs that you have. Simmons is just… I make up it’s a hard school to lead, because, with the social justice impact commitment to the world, I make up, it has to feel like a minefield sometimes. And then I think of Wharton as tough and hard and competitive, and you eat what you kill, is what I really think of. I’m just going to be honest with you. So those are some stereotypes that I’m bringing into your jobs, which may or may not be true. So, I’m curious, in the middle of a crisis, when you take over leadership of something that is complex and challenging, what was it like? Let’s start with Lynn.

LPW: And that we’re personal beings too. So, I said we had to move, we had to start new jobs. Erika and I both had children that were starting college. I was selling the house in Ithaca, New York. Imagine trying to sell a house in Ithaca, New York in the middle of the pandemic. And my oldest was starting his first job as an attorney. So, a new job and, yes, lots of things. My mom was transitioning out of her house, and so it was lots of different things.

BB: Geez!

LPW: Was it hard? Was I scared leading a university that’s grounded in social justice, and one of the few women colleges left, that identifies as women-centered and thinking about that trajectory, and then being in Boston, the uber-college town where I have Harvard and MIT in my background and BU and BC? And so, I’m leading this small women-centered college, and we’re co-ed for grad school, so I had to think about, “What’s a new model for a tuition-dependent business school? How do we bring front and center the importance of women education? How do we keep our social justice mission?” We educate nurses and social workers, who were burned out.

BB: Yeah. Oh God, we’re tired.

LPW: Yeah, they’re tired. All of those were types of things for leading a small, tuition-dependent university, so yeah. But I went back to the principles, we talked about the principles, you talk about it, and I get up every day and try to be the best leader that I can.

BB: What’s one thing… And this is not fair, because Erika will be able to prepare. What’s one thing that you like more than you thought you would like, and what’s one thing that is so much more challenging than you thought?

LPW: So, I can start with the challenging. When you’re a dean, you get to really be more on the ground. So, I got to spend more time with students and faculty and staff. The president, half of my day is outside of the organization, doing advancement work or talking to other presidents or traveling. You kind of miss that intimate time that, I don’t get to go to a volleyball game as much or have lunch with students. What I can say though is, is that both Boston and Simmons has been a welcoming community. Yeah, people don’t think about Boston that way.

BB: No, I do not.

LPW: But it has been an extremely welcoming community and supportive of my leadership journey, my strategy in Simmons and getting to know my team in a pandemic era has been a wonderful experience.

BB: I love that. Okay, Erika, tell me what it was like for you? And then you have to answer my questions, if you will.

EJ: So much the same experience. I relocated from Atlanta to Philadelphia. Left my family because my daughter was graduating high school. So, it was just me sitting in an apartment in Center City, Philadelphia, where I knew no one. The city was boarded up because it was just the week after all the racial protest from George Floyd. The city was shut down because of COVID. Those were dark, dark days. And you asked whether or not I was scared. Scared? No. I think because things were happening so rapidly, the decisions that we had to make were so immediate, that there was no time to be scared. But I do remember, over time, feeling lonely and feeling isolated, and because I’m such a person very much invested in the personal relationships with people that I work, not having any of those personal relationships. It was six or eight months before I met a single person in person, really, in this job. So, I was making decisions around whether to close different aspects of the campus when I had never been on the campus.

LPW: Right. We had to imagine.

BB: Woah.

LPW: Yeah, yeah, yeah. [chuckle] I hadn’t even seen the house I moved in Boston. Had you seen your apartment before or just videos?

EJ: I had to get it site unseen.

LPW: Yeah, we both moved into places in Boston and Philly site unseen, because people weren’t letting you in.

EJ: Yeah. So those were rough, rough days. I will say that, to answer your second question then, what surprised me or…

BB: What was a challenge that was more difficult than you anticipated and what was something that was surprisingly better than you thought it would be?

EJ: So the surprisingly better than I thought it would be, is actually counter to your stereotype of the Wharton School. [laughter]

BB: Wait, let me laugh for a second. That’s good. Set us straight Dr. James. Set us straight.

LPW: Yeah, exactly. I’m laughing with you, Brené.

[laughter]

EJ: So, prior to spending time and getting to know this Wharton community, I too thought it was like you described, that it was competitive, that it was cut-throat, that it was cold, that it was impersonal, that it was all of these things, and I was stunned to find out it was not that.

LPW: So, your Wharton example is like my Boston example.

BB: Yes, exactly, yep.

EJ: Yeah, Yeah.

BB: Fueled on nothing but bullshit, but still real in my mind.

EJ: And the way I found this out was because I started… We were just living through all the racial protests and racial reckoning and whatnot, I was a little anxious about how I, as a Black woman was going to come into the Wharton School and what we were going to do around diversity and would people, within the Wharton community, think, “Oh, she just has a personal agenda that she wants to get pushed forward.” So, I was pretty reticent to do anything around the diversity front. And it was our faculty and our students that set the expectation that Wharton was going to do something, Wharton was going to go out front, Wharton had a commitment and a responsibility to be a part of the narrative when it came to diversity, equity, and inclusion, for example. And that was my indication that this is a school that’s very different from what I thought it would be. And the level of support that I saw, our faculty, “How can we help you? What do you need from us?” It was really tremendous. So, I do want to just clarify for your listeners that we do have the stereotype that you described, but the reality of what this community is like, is very, very different. So that was my biggest, pleasant surprise.

BB: I believe that. And I’ve done that thing too, where I know several of your faculty members and I’m good friends with Adam Grant, and I’m always like, “Oh, they must be the exception.” And Adam’s like, “You need to re-think again. We’re not the… ”

EJ: Yes, think again.

BB: Yeah, and I’ve been there and done talks there, and it was like one of the most fun places I’ve ever been. But I just, I’m holding on to it for some reason. Yeah, I don’t know why, but I love to hear that that was a delightful surprise.

EJ: It was a delightful surprise, yes. And then the biggest challenge that I did not anticipate was… I knew Wharton was big and I knew Wharton was a prominent business school. I didn’t realize how influential it was in the world and how visible it is in the world. So, when a decision is made from the Wharton School, or when we’re launching something or choosing not to do something, it gets known. And I wasn’t fully appreciative at how visible the school is and how therefore visible I was going to be. So, I think that’s been the challenge to recognize, people want to know what we’re doing, and people will have some evaluation or critique and I’ve got to be okay with that.

BB: Yeah, I want to know what you’re doing, and I pay attention to what y’all are doing, and the same with Simmons, not… And even before, that’s why I said yes to the event there during the middle of the pandemic, because I’m curious about what you all are doing, and you’re one of the only few institutions that are still really social justice first focused.

LPW: We are.

BB: And so, is it hard for y’all that people are watching, with criticism balled up and ready to toss?

LPW: It is constantly, and we’re constantly texting each other saying, “Did you see Simmons in the paper? Did you see Wharton in the paper?” And our kids are texting us, saying, “Did you see us?” And so, you’re constantly under this microscope.

BB: Oh yeah.

LPW: And it’s spilled out to our family and our friends too. And so it goes back again to, we’re always having to show up and daring to lead.

BB: That’s it.

LPW: And making sure we’re representing our organizations and their values.

BB: That is it. And sometimes I’ll get a text from one of my kids, I’ve got a 23-year-old and a 17-year-old, so a junior in high school and a daughter in graduate school, that’ll just say, “Oh, hey, Mom, I was on social media. You okay?” I’m like, “Shit.”

[laughter]

LPW: I know.

EJ: You weren’t supposed to see that.

BB: Right. I know. Somehow it feels worse when your kids see it. Because you’re like, “Don’t forget I’m awesome. Hashtag they’re all liars.”

[laughter]

LPW: Right. Exactly. Hashtag awesome mom. [laughter]

BB: Yeah. [laughter] Yeah, I don’t want the people that know me outside of like… I always think I wish there could be like a professional geographic bubble, so like the other moms I hang out with or my friends from the neighborhood don’t see the work take-downs, because then I always feel like they… I go to a water polo game or something, they’re like, “You okay?”

[laughter]

BB: I’m like, “That was a bot, leave me alone.”

LPW: And my daughter’s a dancer, so I go to a dance event, and… Yes. [chuckle]

BB: Oh! That’s tough.

LPW: The dance moms start asking me questions…

EJ: The dance moms.

LPW: Yeah.

BB: The dance moms, like, “Hey, have you read your Instagram comments?” [laughter] I love y’all’s friendship. I just love it. It’s so wonderful to see just two powerful women making the world a better place, who are texting each other like, “What the heck just happened?”

LPW: Right.

BB: Yeah.

EJ: Daily.

BB: Daily, yeah. We need it, right?

LPW: Oh, we definitely do.

EJ: We’re each other’s support team, cheerleader, you name it.

BB: Yeah, that’s it, truth teller.

LPW: Yeah, truth teller, for sure.

BB: Yeah.

[music]

BB: All right. Y’all ready for the rapid fire?

LPW: Yes.

EJ: Sure.

BB: Okay. I know y’all well enough to know that you are preparers. So, if I ask Erika first, Lynn’s going to be like, “Okay, I’m going to have an answer to that.” And then, I’ll ask Lynn… So, I’m going to go back and forth on who gets to go first. Erika, first one.

EJ: Yes.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

EJ: Part of life.

BB: Lynn?

LPW: Putting your ego aside.

BB: Lynn, what is something that people often get wrong about you?

LPW: They forget I’m an introvert.

BB: Oh, hashtag same. Okay. Yes. Erika, what’s something people often get wrong about you?

EJ: They think because I’m kind and nice, that I’m not tough.

BB: Not a mistake I would make. Okay. Yeah. [chuckle] Just saying.

LPW: Yes, she’s tough.

BB: Okay. So, both of you, and I’m going to have Erika answer first, what’s a piece of leadership advice that you were given that was so great, you need to share it with us or so shitty that you need to warn us?

EJ: So great was, a colleague when I was at the University of Virginia said, “Leadership is about managing energy first in yourself and then in others,” and I thought that was profound.

BB: Whoa!

EJ: Managing energy first in yourself and then in others.

LPW: That’s a good one.

BB: I’m not good at the first one. [laughter] Okay.

EJ: Most of us aren’t.

BB: Okay. Lynn.

LPW: So, I got the advice that women often say no because they don’t have the confidence. And so they’ll say, “I can’t do this because this is a stretch assignment. I’m not going to take that promotion.” But instead, and say, “Yes, and what do I need to do the job? Who do I need and what do I need to do the job?”

BB: So are we less confident or… This is so profound for me, Lynn, because are we less confident or have we been socialized not to ask for what we need to be successful?

LPW: Ask for what we need and then take that risk. A man may only do 50% of the job, but he’ll say, “Okay, I’ll take the promotion.” The woman wants to be prepared and have 90% of the skills. But instead say, “Yes, and this is what I need to do the job well.”

BB: I love it. Okay. Lynn first. What’s one thing you’re grateful for right now?

LPW: My family and my village.

BB: Beautiful. Erika?

EJ: I would say my health.

BB: None of us look the same way at that again. Okay. I love this. So, we’ll go Erika first. You gave us five songs you can’t live without. “What a Wonderful World” by Louis Armstrong, “Happy” by Pharrell Williams, “Hello” by Adele, “Celebrate” by Earth, Wind & Fire, and “Uptown Funk” by Bruno Mars. In one sentence, and I have to add this caveat every time I’m talking to academics, that has no semi-colons or in-dashes and is not a paragraph long, in one succinct short sentence, what does this mix tape say about you?

EJ: I desire to see the positivity in life.

BB: Beautiful. Okay. Lynn, your songs, “Golden” by Jill Scott, “I Say A Little Prayer” by Nnenna Freelon? Am I saying that right?

EJ: Yep, a Simmons alum.

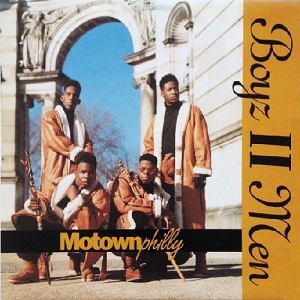

BB: Okay. “Conqueror” by Estelle, “Don’t Stop Believing” by Journey, and “Motownphilly” by Boyz II Men. [laughter] I love you. Okay. In one non-academic sentence, what does this say about you?

LPW: Leadership is about dancing when no one’s looking.

BB: Ooh! What a gift both of y’all are to the world, to… This book, I’m never going to say again, this is my pledge to y’all, I’m never going to say, people, planet, profit without saying preparedness.

LPW: Thank you.

BB: Then I will reference where I got that from.

EJ: Awesome.

BB: Yeah, because it’s so good, it’s so smart, and it dovetails so powerfully with just what I know about courage and vulnerability and showing up, and doing hard things, which is why good leadership is so rare, right? It’s just… It’s so good.

EJ: Thank you.

LPW: It complements all the great work you’ve done, and thank you.

BB: Yeah, it’s just wonderful. Thank y’all for being on Dare to Lead, and thank you for the book. Yeah, I’m grateful.

EJ: We’re grateful.

LPW: We’re grateful too.

EJ: Thank you, Brené.

LPW: Thank you.

BB: Thank y’all.

[music]

BB: God, I feel so lucky to be able to have conversations like this. So, did you learn a lot, Barrett?

BG: I did. I did.

BB: Anything stick with you? She’s consulting her 5000 pages of notes in her…

BG: I love what Lynn said at the end, that leadership is about dancing when no one is looking.

BB: I mean those two pieces of advice, leadership is about dancing when no one’s looking, and also what Erika said about managing your energy first and then other people. I mean, wow. I’ve got to learn how to manage my energy. [laughter]

BG: Same.

BB: I thought you were going to say you do. That was the look on your face.

BG: No.

BB: I’m glad y’all are here. If you want to find a copy of The Prepared Leader: Emerge from Any Crisis More Resilient Than Before, wherever… Get that wherever you like to buy books. It’s such a fast, digestible, easy to metabolize, hard to put into practice, but easy to understand book of knowledge and wisdom. I love it. You can go to our episode pages on brenebrown.com to find links to more information about Erika and Lynn, where they work, their work, Wharton, Simmons, it’ll all be there along with transcripts. Thank you for being back with us on the Dare to Lead podcast and stay awkward, brave and kind.

[music]

BB: The Dare to Lead podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and Kevin McAlpine, and the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2022 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.