Brené Brown: Hi everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

BB: Welcome to Part Two of our two-part series with Karen Walrond. Writer, activist, long-time friend. We are talking again today about her new book, The Lightmaker’s Manifesto. In the first part, we talked about activism, how we define it, where does the word come from? What does it mean? And how does it show up in our daily lives? And in this episode, we talk about the connection between activism and spirituality, we talk about listening to whispers that are calling us, and we talk about really deep self-inquiry strategies that help us know what we’re supposed to be doing. Oh God, I love this conversation so much. We also… We go there, because we talk a lot about performative activism, performative outrage, the bullshit that makes us all crazy. We talk about when to be in public and when to be in private with our work. It’s an important conversation, and it’s a conversation that we need to be having right now. We also talk about the realities of activism burnout and how joy helps curb some of that. I’m glad you’re here, Karen Walrond, part two of our conversation.

[music]

BB: Before we jump in, let me tell you a little bit about Karen. I went through this bio during our first episode, but in case you’re jumping in in Part Two, because you’re a rule breaker and you listen to things out of order, I really like that sometimes, Karen is a lawyer, a leadership coach, photographer and activist, she is wildly convinced that we are all uncommonly beautiful. In fact, her first book, The Beauty of Different: Observations of A Competent Misfit, provides irrefutable evidence that the thing that makes us different is the source of our super power. Her current book, The Lightmaker’s Manifesto, helps us name the skills, gifts, values, and actions that bring us joy, identify the causes that spark our empathy and concern, and then she weaves it all together to help us understand how lasting, meaningful, impactful change happens. Born in Trinidad, and Karen currently lives in Houston with her British husband, Marcus, and their American daughter, Alexis. Welcome back, Karen.

[music]

BB: Welcome back, Episode Two.

Karen Walrond: I’m so happy to be here as always.

BB: The Lightmaker’s Manifesto. We’re talking about your new book. In the first part, we’ve talked about what it means to be an activist, what it doesn’t mean.

KW: Yep.

BB: We’ve talked about some of your early work with the one campaign.

KW: Yep.

BB: We talked about our experiences of Harvey and how we think back on those as traumatic, but also joyful, weirdly.

KW: Yes, yeah.

BB: But you said something that was incredible, that joy can abut pain, and often does.

KW: Yeah.

BB: You helped us understand the difference between happiness, which… I mean, this is exactly what we see in the research. More circumstantial, more fleeting, joy driven by purpose and meaning.

KW: Absolutely.

BB: And in this episode, I want to jump right in.

KW: Okay.

BB: What was your hypothesis about the relationship between activism and spirituality? Did you have one?

KW: At the beginning, I suspected that most people who were activists probably… I knew they believed in something bigger than them, and I assumed that was God or the universe or some sort of spirituality. And what was surprising was that some of the people I interviewed were faith leaders, some of them do have a strong faith. But some were agnostic, some were atheists. Those who did practice faith, practiced a variety of different faiths. But that activism might be spiritual in and of itself, which was something I hadn’t really considered, and it was sort of a learning that I kind of put together after speaking to two people, both of whom were theologians, one of them is a priest or a minister at the church of Canada, Aaron Billard, and then the other one is actually the head of the Jung Center here in Houston. He has a degree in theology, but is actually a clinical therapist.

BB: Are we talking about Sean Fitzpatrick?

KW: Sean Fitzpatrick, thank you. Yeah, you know Sean who is just a great, great guy.

BB: Okay. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

KW: And I spoke to both of them sort of one right after the other, so it was a really very Aha thing for me. And so Aaron was actually the very first person I spoke to about the book, I think, and he had talked about, for sure, that activism is a spiritual act. That he felt like usually, you’re doing something for somebody, and that the way he does his work with Unvirtuous Abbey, which was this amazing Twitter feed.

BB: Pause for a minute and just tell people what that is first.

KW: Yeah. So Unvirtuous Abbey, when I first heard of it about probably 10 years ago, it was an Abbey that existed virtually, and there were virtual monks, this person said, and they tweeted about basically pop culture and faith, sort of the intersection of those two things. But it sort of pokes fun at Christianity in a lot of ways, and it pokes fun at some of the more rigid aspects of Christianity, while also reminding people that we are all interconnected and that everybody is worthy of love and belonging. I found out after following them for a long time, that the person behind the Twitter feed knows faith and knows theology, but I assumed it was just somebody who was a pretty active Christian.

BB: Secular person? Oh, you assumed it was an active Christian?

KW: Yes.

BB: Yeah.

KW: What I didn’t realize that it’s actually a minister. It was actually the leader of a church, which is pretty amazing, because it can get pretty irreverent, but never in a mean-spirited way.

BB: Never irreverent about God or faith.

KW: No. About the church.

BB: But irreverent about the man-made.

KW: Yes.

BB: And I say that word with all intention.

KW: Yes, yes. Definitely about the institution of Church, but never about faith at all. And so, Aaron is lovely and he’s exactly the kind of person that you would want a faith leader… He’s very calm and very sweet, but he’s really into Star Wars, he’s really into just any pop culture.

BB: I like him already.

KW: He’s wonderful. And he talked about how for him as a church leader, a lot of what he does is about worshipping, but you don’t have to believe in God to do the spiritual act of activism. So I thought, “That’s so interesting to me,” but also, he’s actually a faith leader, so he would say that kind of thing. So that’s when I turned to Sean, the head of the Jung Center and the therapist who was raised Catholic, but I think if you asked him what his faith practice… He would say it’s complicated, kind of thing. And he’s talked, defined spirituality as experiences of meaning. That really, spirituality at its root, is about creating experiences of meaning. And of course, with activism, often that’s what we’re doing. We are creating or doing something that creates meaning in the recipient’s life, but also in your life, and you’re doing things that sort of tap into your own purpose, and that in and of itself can be a very spiritual act. So it was a really interesting way to sort of think about it, that you don’t necessarily have to practice a faith, but you still get the sort of transcendence that practicing of a faith can do when you are engaged as an activist. And of course, that can often lead to joy.

BB: Yeah, it’s so interesting because in our research, we define spirituality as the belief that we’re inextricably connected to each other.

KW: Well, there you go. Right?

BB: Yeah.

KW: That’s why we’re activists.

BB: I love wrestling with these questions with you, because, how many times or how often do you think I’ve called you or maybe vice versa and said, “I think I want to become an Episcopal priest.”

[laughter]

KW: Yeah, both of us were sort of wrestling with that at the same time, yeah.

BB: Yeah. And then maybe we will go off together to the coast of Oregon.

KW: Yeah. I mean, right?

BB: To a seminary and become Episcopal priests. [laughter] And then we could have a church together.

KW: That would be terrifying and wonderful.

BB: Our Lady of Back The Fuck Up. [laughter] That’s what we could call it.

KW: I’m in, that’s it. I think we would be overrun with members, [laughter] I think, if we did that.

BB: Yeah, I want to read something from your book.

KW: Yeah.

BB: You write: “There it is. Activism when approached with an intentional mindset is all about creating experiences of meaning. Activism means taking responsibility to find answers to the world’s problems, dedicating yourself to a cause greater than your own interests. Activism doesn’t require a faith home or a spiritual practice, yet activism can feel very spiritual in nature.”

KW: Yeah. Yeah, that makes me want to do it. Right?

BB: It does. Alright, tell me about listening to whispers. [said in whispered voice]

KW: Yeah, that was one of the surprises of the book, was I asked people, how did they get started? And some people said, “Oh well, this really awful thing happened to me, and that could not stand.” There were a few people that were like, “No, no, no, no. That is wrong, and it happened to me, and now I have to do something about it.” But then there was many, probably more people who said things like, their entry into activism was because something just wouldn’t let go in the back of their head. That doesn’t seem right. That doesn’t seem right. And even if they tried to put it away, it was like, “There’s got to be something I can do to make this better. And I’m nobody, but maybe there’s something little I could do.” And more than one person described that as a whisper, as sort of this little thought that’s like, “That can’t be the way the world is supposed to be.” And I feel like that’s probably more how a lot of us get into activism, that a lot of us are like, “Really? That person gets treated that way just because of that?” or, “The law says this and ignores these people?” Or something like that, and it won’t let us go. And so the advice many people said is, “That’s your clue. That’s the universe telling you, there’s something here that you need to pay attention to.”

BB: There’s something about the connection, and I don’t know if I’m connecting these things, so tell me if I’m making a connection where there’s not a connection.

KW: Okay.

BB: So you sent me a book, I don’t know, a couple of years ago, maybe a year ago, by Mira Jacob. Good Talk?

KW: Jacob. Yeah. She’s amazing, amazing woman. She had a whisper.

BB: Did she have a whisper?

KW: Yeah.

BB: What an incredible book. This is a graphic novel, and it’s just…

KW: It’s graphic memoir, it’s her real life. Yeah.

BB: Oh, yes. Graphic memoir. Yes, yeah. It’s just so incredible. Tell me about this, “Where have I never been before?”

KW: Yeah, yeah. So Mira, who’s just a dear lovely woman, she is a novelist sort of by trade. She’s a creative writer.

BB: And very well-known and prestigious.

KW: And very well-known, very critically acclaimed. Her first book was called, A Sleepwalker’s Guide To Dancing. Beautiful novel. And people who read the book kept saying, “What’s the sequel? Where is the sequel?”

BB: Yeah. “What’s next?”

KW: “What’s going to happen to these people?” Because she writes beautifully and vividly and speaks that way as well. And she knew that there was never going to be a sequel, and it was starting to frustrate her that everybody wanted these characters to continue living. And she knew that that was not going to happen. And so she was expressing this to a friend, an architect, and he said, “Look, whenever I don’t know what I’m supposed to do next, I look at the topography of my life. I think of my life as a topographical map, and I wonder, where have I never been before? That’s probably where I should go.” And so for her, as she thought about that, one of the things that she had always done to help her write her books, was draw and doodle. If she had a problem trying to figure out a plot line or something, she would just draw and it would eventually come to her. But she’s not a trained artist, she just liked to doodle. And she suddenly realized, “I think I need to draw my next book,” and that’s how Good Talk came to be. But she taught herself basically, the software to create what eventually became the book.

BB: That is the nuttiest thing, because it is so incredible.

KW: It’s so good and you would never know that. And what her book ended up being, which was basically her grappling with the issues that were arising in her life as a South Asian woman married to a Jewish-American man with a mixed-race kid, and sort of drawing the conversations that were happening, it has turned into what I think is one of the best anti-discrimination books I’ve ever read.

BB: Oh God, yeah.

KW: It’s such a…

BB: Humanizing, real, in deep context, story-telling…

KW: Story-telling. And it’s about things like immigrants, colorism, racism, LGBTQ issues, it touches on every single thing.

BB: It’s just human.

KW: And it has become… I have bought and given away more copies of that book for people who are grappling with, “How can I be an ally?” Because it’s such a wonderful way to do that. And she is an activist through that book, simply by listening to the whisper of, “Maybe I should draw something, maybe I should draw what’s happening and see what happens.” And it got there.

BB: Okay. One more question from the book and then I’ve got a lot of big life questions for you, because I need some answers.

[laughter]

KW: Let me take some water here.

[laughter]

BB: Yeah. We’re both chugging down some Topo Chicos. Probably the worst thing to drink while doing a podcast.

[laughter]

KW: Exactly.

BB: Like warm tea or something, now we’re drinking kerosene-fueled water. [laughter] Tell me about Speak, Write, Shoot.

KW: So, the big part of this book is about… First of all, if anybody thinks that this book tells you, “This is how you’re an activist.”

BB: Yeah, no.

KW: That’s not what this book does. But what this book does talk about is, “Here are some ways to do some self-inquiry so that you can discover that for yourself, or how to be an activist for yourself.” And so, right after I met you, after I realized I can’t be a lawyer anymore…

BB: I was there for it. It was an amazing unraveling.

KW: It was an unraveling. It was an unraveling. I would not have used that word, but that…

BB: It was totally an… It was so beautiful.

KW: Oh, thank you. It didn’t feel that way. Damn vulnerability.

KW: But when I decided that I couldn’t practice law anymore, that it wasn’t where I wanted to be, it was the first time I’d ever made a decision like that without a plan. When I left engineering, I was like, “I’m not going to be an engineer, so I’m going to go to law school.” I had always made a plan. If I left a company, it’s because I had a job offer at another company. So what I did was I made a list of everything that I love to do, to see if I could just get a clue of where I wanted to go in my career, where I wanted my work to be, what I wanted to stand for. And for me, the prompts for what I did are in the book, but for what kept coming up, was, I love public speaking, I love writing, and I love photography, and whatever I do, either as a career or as a way to be of service, I wanted it to include as many of those three things as I could. Speak, Write, Shoot. Public speaking, writing, or photography. And I did that back in 2008 when we met, and I have never not done anything that didn’t involve two of those things. Even right here, I’m talking about a book, it’s writing, and we’re speaking.

KW: So for me, as much as I can do that, that’s where I derive a lot of my joy. And if I can do that in a way that taps into purpose and meaning for me, then more is the better. Life gets really, really good, because it’s fun for me to do. I enjoy it. And what’s interesting about it is it’s not necessarily that I’m great at all of those things. I want to make that distinction. I was a really good lawyer, but if I wanted to be a civil rights lawyer, that for me would not bring me a lot of joy, because even though I could do it, it’s not something that I really love. So this is about tapping into, what is it that really lights you up? I love doing this. I may not be the best speaker in the world, I may not be the best writer or the best photographer, but I love doing those three things. And if there’s a way I can tap into that to be of service, then it’s best for everybody. And I’m less likely to burn out, because those are the things that I love.

BB: Yeah, I did that. We didn’t sit down and do the exercise together, but I think over the past 15 years, 10 years, we have both really had that reckoning.

KW: Sure.

BB: As part of our unraveling.

KW: Yes.

BB: I was in the middle of my unravel when I went to Oregon, which is probably the only reason I said yes to it.

KW: Then maybe that was true of me as well, right?

BB: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I think for me it was, connect the seemingly unconnectable.

KW: Those are your light words? Yeah.

BB: That’s my thing, that’s… Yeah, connect the seemingly unconnectable. If activism is born in that place…

KW: For sure.

BB: I wade into some hard shit.

KW: Yes. Why you made it into the book? Because I’ve watched you do it.

BB: But if I’m doing it because I have to, the pictures that people send, of them burning my books, I get all kinds of crazy stuff, death threats, I mean just shit, are so almost insurmountable for me emotionally. But if I come to share my activism by connecting the seemingly unconnectable, I don’t feel fireproof, but I feel on fire.

KW: Yeah.

BB: Do you know what I mean?

KW: Deeply, yes.

BB: Yeah.

KW: Yes. And also, it’s very similar to the work that you talk about, about your values will light the way. When you’re very, very clear about who you are and what you stand for, then a lot of that other stuff starts to roll off your back a little easier, because you are so focused on, “No, this is where my meaning is.” So if other people are having a problem with it… It’s not that people close to you are saying, “No, this is not right,” that you’ll probably listen, but if the total strangers come in off the street, and say, “That’s not right, you shouldn’t do that.” You’ve done the work to know, this is where I’m supposed to be, right? This is the work I’m supposed to be doing. And it makes it a lot easier. And again, just to tie back, this is not necessarily about the things that you’re good at, although if it lights you up, you probably get really good at it.

BB: I mean, that’s it. That’s it.

KW: You probably do. But those are the other things that people think you’re really good at that you’re just like, “That’s cool, I’m glad you appreciate that. But that’s not what’s lighting me up”. So it’s really… You have to really look at the thing that really hooks you.

BB: Yeah, and activism from that place, for me, not only is more effective, it’s more sustainable for me.

KW: And that’s everything. That’s everything, because the truth is that a lot of the things that we are working toward in social justice aren’t going to be solved in our lifetime.

BB: God dang it.

KW: I know. That was some wisdom from Valerie Kaur that I got when I wrote this book. And it was depressing, but it’s also very freeing.

BB: It is freeing.

KW: Because now you know, “Oh, this is about the journey, this is not about the end goal as much anymore.” So it is very freeing.

BB: Okay. Can we play a game?

[laughter]

BB: Like Ellen DeGeneres here? Can we play a game? Before we get to the rapid fire.

KW: Alright.

BB: I’ll take a swig of my cold Topo Chico, please hold everybody.

[laughter]

[music]

BB: I’m going to have you solve some activism proofs for me. Some difficult challenges. Are you ready?

KW: Proofs? Yeah, like Mathematics. We got it. I can do this.

BB: I’m going to keep the language as clean as I can.

KW: Why?

[laughter]

KW: Why start now?

[laughter]

BB: Okay. You know, probably better than most people, that I really wrestle with how much of my life has to be public in order for me to get my work into the world, right?

KW: Yeah, sure.

BB: And I am very private about a lot of my activism.

KW: Okay.

BB: But how do we handle it when people publicly come at us and say, “You didn’t speak up about something that happened in this small town in Iowa, and therefore you’re awful.” What is the price you pay when you don’t want to engage in performative outrage and activism? And I know you wrestle with this.

KW: Sure. So this is such a great question, and I think it’s probably particularly difficult for people like you who have very public platforms, because there’s sort of this expectation. And in some ways, I think there’s validity to this, that if you have a platform that you will use it, for good. And I think that is a fair assumption.

BB: Agreed.

KW: That if you have a platform, you’ll use it for good. Where I think it feels uncomfortable, is that people will want to tell you how that should look and who you should serve that for. Who you should use your platform for. And I would argue that nobody gets to determine that, but you. So there’s two parts to this. The one part is, if you use your platform in service of whatever cause, that you have to be very clear that these are the causes that are important to me, and again, if people call me out, if I don’t use it for that cause, then that’s on them, right? I’m very clear. That’s one part. The second part has to do about how public do you have to be, if at all?

BB: Yeah, because you don’t talk about this. We do advertise what we do all the time.

KW: And in a lot of ways, it would feel weird for me to advertise. And I’m sure for you.

BB: For sure.

KW: Yeah, so for me, like the line that I draw is, I will say something if my saying something will help activate other people, I will not say something if it’s about, “Look how cool I am,” if that makes sense. And that’s a really strange line to do this because activism, I think is always, remember at the beginning, it’s in service of other people, right?

BB: Right.

KW: And you can be of service to other people without the entire world knowing about it. The whole world does not need to know that you gave X amount of money or the whole world does not need to know that even you’re passionate about this one cause. This could be a very private cause for you. This means something for me. Let’s say mental health is something… Is a cause that… Mental health might be a cause that I want to do a lot for, but it also is because there’s some very personal reasons around why that’s important to me, so I’m not going to tell people about it, I’m just going to do what I can behind the scenes and do that. So the problem is that we live in a time where if you have a latte that looks pretty, you’re expected to kind of share it. And there’s this sort of expectation that you share everything in your world. And to me, when you start to get to the point where the sharing is more important than the work…

BB: That’s the question.

KW: Right? Then that’s not activism. That’s about your ego, right? That’s about stroking your ego, that’s about other people feeling like maybe they’re not doing enough, so they want you with your platform to do it, and so that they can live vicariously through you about this cause that really has nothing to do with you. So there’s all kinds of other things that gets really tied up in that. So for me, I think it’s far more about, as you say this all the time: “What’s in service of the work? What’s in service of the work?” And that is your discernment. Does that make sense? I feel like I rambled.

BB: No, no, no. Oh my God, no rambling, at all. It makes total sense, and it makes sense to me as someone who is on both sides of it, because I’m not even really talking about me with a big platform, I’m talking about my resentment toward my neighbor who we share the same politics, but why isn’t the sign up in your yard? Like, this is a true story. And I asked and they said, “We just don’t do signs.”

KW: Yeah.

BB: And I was like, “Well.” Yeah. And so…

[laughter]

KW: Yeah and I also think we have a very mutual friend who I won’t mention here, but she is one of the most activated people I know, and I think most people would never know about…

BB: Oh that’s right.

KW: And so she’s one of those people that, as I made that list at the very beginning, at first her name was on it, and then I thought, “She’s not really public about all of this work that she does behind the scenes, I don’t know if she’s comfortable being interviewed with this.” And so I thought, “You know what? I’m not even going to approach her with this because all of this very deep work that she does in her own life, she sort of does it and I think prefers a little bit of the anonymity around doing it,” which I have to respect.

BB: It’s really interesting when I was doing the research for Atlas, I got to self-righteousness.

KW: There you go.

BB: Yeah, and looked at the difference between what is self-righteousness and what is righteousness? And the difference is, righteousness is about taking a position when you believe somebody or a community, somebody has been wronged, there’s a real inequity issue or a justice issue, and you take a stand and that’s righteousness. Self-righteousness is making sure that you prove to yourself and others that you’re doing it.

KW: There it is.

BB: Do you know what I mean?

KW: There it is. That’s it.

BB: That was such a shocker to me when I was researching those terms. Sustaining activism is, I think an inquiry that dates back to the beginning of activism. We’ve always wondered, how can you get involved, to be activated and sustain that? I think one of the biggest killers of sustainable activism is performative outrage.

KW: Oh my gosh. I was talking to a friend of mine the other day. Do you remember right after… I don’t know if it was after the previous presidential election, or if it was in response to sort of the Trayvon Martins, George Floyds of the world. But… People wanted to wear safety pins on their clothing in America. Do you remember the safety pin movement?

BB: I do.

KW: And it was something like it was a signal to people of color that I, a white person with the safety pin, I’m safe for you.

BB: Yeah. I’m safe.

KW: And I just remember laughing because I thought, I can’t imagine any situation, as a person of color, that if I saw somebody wearing a safety pin, that I would approach them and go, “Can I just sit with you for a second?” I just can’t imagine that ever happening, and that was, to me, was so much more about performing “See, I’m safe,” than it was actually doing some work to make spaces safe, which is harder and more painful.

BB: You think? Than buying a safety pin? Yeah, yeah.

KW: Right, and it requires a bit of accountability on your own part, right? And to me, that’s a perfect example of sort of that self-righteous that you’re talking about, that it’s, “Look at me being woke.” I hate that word, but woke or being a good person. Being an ally, as opposed to actually maybe not saying that at all, but being an ally.

BB: Being it. Yeah, yeah. That’s interesting. It’s such an important book, Karen.

KW: Thank you.

BB: I have one more question.

KW: Go on.

BB: Oh man.

[chuckle]

BB: This goes back to some really intense debates.

KW: Okay.

BB: I used to teach a Global Justice course many years ago at the University of Houston at the Graduate College of Social Work, and my co-teacher was Jody Williams, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for her work on banning land mines. And I would put her in the activist category.

KW: Yeah, I can see how it fits it. Yep.

BB: Yeah. And Nobel Peace Prize winner, and so…

KW: That’s a good tip.

BB: It’s a good tip.

KW: It signaled that maybe she did.

BB: Yeah, but there was a really old debate, and maybe there is no answer, maybe it depends, but I have been an activist and been around activists probably since my very early 20s, so that puts me solidly in three decades.

KW: Okay.

BB: And the burnout rate is just really…

KW: Sure.

BB: Especially now at my age, looking back at the other people, my contemporaries that are my age, I wonder how long we can fuel activism on rage versus what you’re talking about in this book. And don’t get me wrong, I know rage.

[chuckle]

KW: Yeah, yeah.

BB: Yeah. But rage activates me in a way that burns… That fuel burns really hard and really hot and really fast. And the fumes of it are poisonous.

KW: Yeah.

BB: It can propel me pretty far.

KW: Yeah.

BB: But it almost poisons me as it’s fueling me.

KW: I say in the book that I’m very pro-anger. Like I think anger and rage can be incredibly motivating.

BB: Yeah, for sure.

KW: The trick is that it might be the spark but I don’t think it should be the fuel.

BB: Oh my God, this is what I’m saying.

KW: Right?

BB: Yes, I think it can be one of the most effective catalysts.

KW: Sure.

BB: But I don’t think it’s a long-term companion.

KW: No. The fuel is the learning, the self-compassion, the staying in your values, the kindness, the measured-ness, the purposefulness. That’s the fuel. The spark is the rage, right?

BB: Yes.

KW: The Spark is what… That’s it. That’s the thing. And so I talk about kindness, and I talk about compassion, I talk about self-compassion and I don’t really talk that much about rage in this book, because rage is going to happen. Like rage is what got us here. Rage is what makes you go, “Something’s got to change.” But what we tend to do is, we tend to react in rage and go, “That’s it, we’re going to say the mean things to the other side, or we’re going to do something hugely radical,” and nothing against radical, I love a radical.

BB: Same.

KW: But at some point, you’re going to have to be, “Okay, I’ve got to regroup. I’ve got to get my energy back. I’ve got to have some self-compassion for myself. If I react in rage and just without anything else, I’m going to say something that isn’t me that I don’t like or that doesn’t actually help. It actually just makes things worse.” So the rage needs to be the thing that sparks you going, “Okay, how are we going to fight this? Let’s think about this. How am I going to be able to know when I’ve been doing so much that I’m starting to get a little bit burned out and maybe I need to tap out or ask somebody else to sort of take the mantle and let me just take a breath so that I can re-gather that energy to go right back in.” Our friend Valerie Kaur talks about, breathe and push, right? And it’s not breathe all the time, or nothing will ever get done, and it’s not push all the time because you can’t… It’s about that sort of rhythm of being able to, “Okay, let me gather my energy. Okay, let’s go in. Let’s do something, let’s create the movement, let’s mobilize the march, let’s do.” And then you take a breath and it’s very, very rhythmic. So yeah.

BB: The inhale and the exhale.

KW: Absolutely.

BB: John Halifax, yeah.

KW: Yeah. Absolutely.

BB: Wow, thank you for being on Unlocking Us.

KW: Oh my gosh.

BB: This is so good. Are you ready for some rapid fire?

KW: Yeah.

[laughter]

BB: How many… No.

KW: Don’t start. You know? This is why…

[laughter]

KW: Look, everybody who’s listening, never get on a podcast with your good friend. They know your secrets.

BB: So many.

[laughter]

BB: Okay, look, I was going to do two sets of rapid fire, one for each podcast, but I’m just doing one because I love you.

KW: Aww you’re so kind to me. You just give.

BB: I am. And give.

KW: And give.

BB: Okay. Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

KW: A pain in my ass.

[laughter]

KW: Vulnerability is a pain in my ass, I’ve been doing it too long. But it is also the secret sauce, it really is.

BB: That’s just like probably the best answer on the whole podcast.

[chuckle]

BB: So you, Karen, are called to be very brave, but your fear is real and you can feel it in the back of your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

KW: I do Kristin Neff’s Self-Compassion Break.

BB: You do?

KW: Absolutely. It got me through Harvey. So I stop to take a breath, I think to myself, “This is hard.” And I remember that this is hard, but then I also think, “But it’s totally normal for this to feel hard. This is exactly what it’s supposed to feel like. It is hard.” And then I say a prayer that says, “Just, let me go gently. Let me be kind.” And move in.

BB: I have goosebumps.

KW: Yeah, I absolutely do it. That was one of the best things I’ve ever read, was that. And it’s in the book.

BB: Love it. Okay. What’s something that people often get wrong about you?

KW: I am extremely sensitive and prone to crying very, very easily, and most people don’t know that.

BB: Last TV show you binged and loved?

KW: Only Murders in the Building. Have you seen that?

BB: Oh my God I’m obsessed. Stop because I’m on four.

KW: Isn’t it smart? Oh well, then I’ll stop, but it’s such a smart show. I loved it.

BB: It’s so smart.

KW: And I love Steve Martin… It’s funny, I’ve loved Steve Martin since he stopped doing stand-up, like I’ve loved everything he’s done after his stand-up.

BB: It’s really smart. Okay, favorite movie.

KW: Oh man, that changes all the time.

BB: It’s okay.

KW: The one that comes to mind is Black Panther, it’s just brilliant. You know what, it’s brilliant… The reason I loved it is because as a Black immigrant, I found that my Black was not Black enough as a kid… As a kid, because most kids only know the world around them, and I thought that the tribes that were shown in Black Panther and all the very different ways that it could look and be was incredibly freeing for me… Black Panther was very meaningful for me, for that reason.

BB: I really love that. I thought it was some of the best storytelling that I’ve ever seen and the acting, just the whole thing, it’s…

KW: And the joy that kept coming up.

BB: The joy and the laughter.

KW: Amazing. Amazing.

BB: And the solidarity.

KW: Yes. And the standing in your values.

BB: And the standing in your values and the refusal to look at Blackness as a monolith, like you said.

KW: Absolutely. That was huge, that was huge. I can’t imagine what that would have done for me as a young Trini moving to America, feeling like I didn’t get the jokes… I didn’t get the inside jokes. I was too Black to be accepted in a lot of the white spaces, and too non African-American be accepted in African-American spaces. And if I had seen that and realized, oh, there’s so many different ways, I think I would have been a lot more confident a lot earlier, for sure.

BB: I don’t think we’ll ever be able to correctly estimate the power of that movie for people.

KW: Yeah, it’s amazing. Amazing film, and a lot of cool action and stuff like that.

BB: Yeah, but you know, you hear all these words and all these terms, and I think about how much of it was in one film, like you hear Black excellence, Black joy, Black diversity, they just brought just… Yeah.

KW: They brought it. It was beautiful.

BB: Yeah. Okay, a concert you’ll never forget.

KW: I’ve been to a lot of concerts.

BB: I know you have.

KW: Oh gosh, I saw BB King in a very, very small club here in Houston, like sitting as far away as I am sitting from you right now. And that was pretty spectacular.

BB: Wow.

KW: Yeah, I hadn’t thought about that one in a while, actually. I was thinking about a bunch of like I’ve seen Prince. I’ve seen some really… Saw Michael Jackson… Or The Jackson 5 actually. So that was my first concert, but that one, the intimacy of that concert was pretty great.

BB: Wow. First thing I think of when you say that is now, both of our kids play BB King on the guitar, because they have the same amazing guitar teacher.

KW: That’s right, that’s right. Shout out to Leland.

BB: Shout out to Leland. Okay, favorite meal.

KW: Pelau, which is a Trini meal. It’s the comfort food of my childhood and the comfort food of my current home, and I feel like every country has their sort of chicken and rice dish. And so that is ours in Trinidad. And it’s chicken browned with brown sugar, caramelized brown sugar and rice and coconut milk, and it’s good. [laughter] It’s good.

BB: Do you cook it?

KW: All the time, I’m actually making it this weekend, actually, my mother’s birthday, we’re celebrating, and I’ll make it for that, so… Yeah.

BB: Does your mom cook it?

KW: Yes. Everybody… Look any Trini cooks it. It is literally one of… Possibly the national dish of Trinidad. Every Trini knows how to cook it.

BB: What’s on your nightstand?

KW: Too many books. Books that I’ll never get around to reading. A lamp. My phone usually because it’s my alarm clock and prayer beads.

BB: A snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life right now that just gives you true joy.

KW: So while it’s starting to feel like fall, and even though I am a tropical Trini girl through and through, I have to have a fire… The rule in my house is if it drops below 50 degrees, we light the fire. Yeah, so it would be… So we’re getting to this time when Marcus and our daughter, Alex and I are each under blankets in our family room watching a movie with the fire going.

BB: That’s good. Okay, tell me one thing that you’re deeply grateful for right now.

KW: You! I am so grateful for you and your friendship for sure, for sure. Thank you.

BB: God, I feel the same way.

KW: Yeah, you. 100% you.

BB: I feel the same way. We have been able to call each other during really fun times and really shit times for a long time.

KW: Yeah, yeah, yeah, one of my favorite memories of you actually was when I opened the pod, after we were moving back into our house and this tiny pod showed up with all that we were able to salvage in our house and really sort of hitting me how very little we had after Harvey, and I opened it and you had texted me serendipitously about something else, right in that moment, and I decided to return your call and I was like, “Brené I just opened my pod and there’s nothing in it. Oh my God, we lost everything.” And you… Everybody should have a social worker as a friend because you were like, “Okay, what you’re feeling is trauma, and that’s totally normal,” and you just sort of like, “Here’s what… This is okay, you’re fine. You’re going to get through this.” And it was so helpful. It really was. It was amazing.

BB: I’m really having a hard time not crying because I could hear in your voice.

KW: That it was bad. That was the first time I broke down and it was a year… 18 months later, and it was the first time that it hit me what had happened, and I was just so grateful… Literally… And normally, I would have texted you back, but I just called you and you were like, “What the hell is wrong with you?” And I was like, “There is nothing in this pod.”

BB: I think… I would have thought probably like you were thinking it would be a Harry Potter moment, and I’d open the pod and my whole house would be in there. And that I just need to move it.

KW: “Aww… all the things that we saved.” Some of it was trash, some of it… Like you could tell… We were like, “This is garbage but I’m not going to throw it away.”

BB: It’s salvageable.

KW: Yes. I’ll figure it out.

BB: Okay, we asked for five songs for your mini mixtape on Spotify.

KW: This was fun.

BB: Okay, and you gave these, “Keep Jammin’ On,” by… Is it Kes the Band?

KW: Kes the Band.

BB: Kes the Band. “Made For Now,” by Janet Jackson.

KW: For sure.

BB: “March March,” by The Chicks.

KW: Yup.

BB: “I Give You Power,” by Arcade Fire and Mavis Staples. Goddang! That’s a good song.

KW: Such a great song.

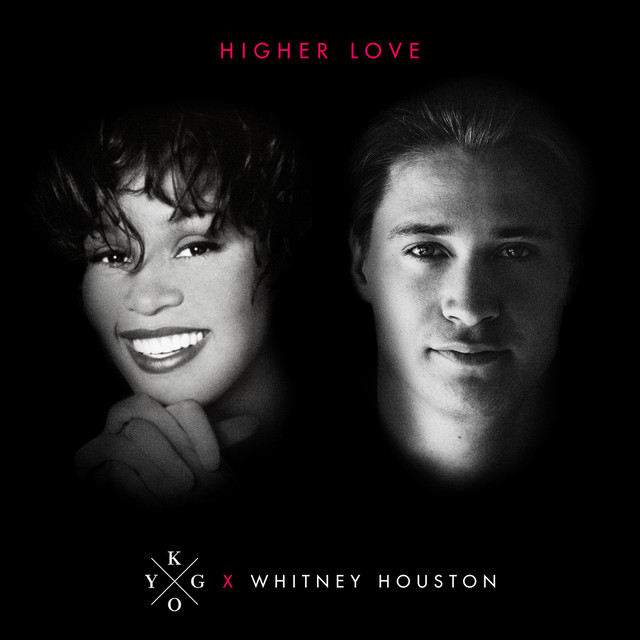

BB: Oh, “Higher Love,” the remix by…

KW: Kygo and Whitney Houston.

BB: Whitney Houston. Okay, in one sentence…

KW: I hate this part.

BB: I know… What does this mixtape say about you, Karen Walrond?

KW: This mixtape says that I am a proud Trinidadian who believes we all have the power to change the world and make it brighter.

BB: You are a beautiful person.

KW: Likewise.

BB: Thank you.

KW: Thank you very much. Such a joy to be here.

[music]

BB: God I love this conversation y’all. I needed this conversation, and the fact that we got to do it in person, like locking eyes with each other, so meaningful. I’m grateful for technology and that COVID did not shut down the podcast, and I was able to do it from closets in the podcast room and all over from anywhere, as long as I have my little portable kit, but I’m also so grateful for the ability to be in person with people, I hope some of that comes back soon, all of the links, how to find Karen, where to find the book, are all on brenebrown.com, and you can find everything you need there. Thank you for being with us on Spotify. Stay awkward, brave, and kind y’all.

[music]

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. It’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.